Dickens on the Web > Delmonico's Dinner Honoring Dickens

The Charles Dickens Page

The New York Press Club Dinner Honoring Charles Dickens

Delmonico's Restaurant, New York City - April 18, 1868

By Herb Moskovitz

As presented to the Friends of Dickens New York, December 2012.

Reprinted with permission of the author

Published on this site August 26, 2015

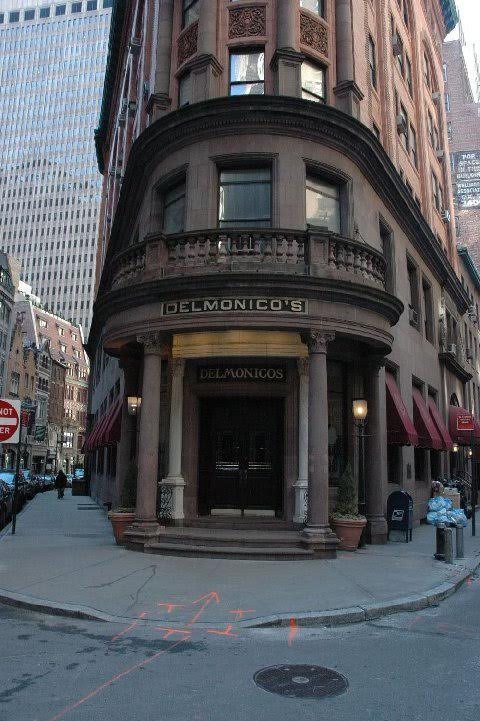

On April 18th, 1868, there was a large press dinner for Charles Dickens at the famed Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City. Today the name of Delmonico's brings to mind a long closed upscale restaurant of the 19th century that features in a song from Hello Dolly or an expensive but not very good restaurant in Lower Manhattan today.

Actually Delmonico's was a remarkable restaurant in Dickens's time and deserves our special attention.

Does anyone know how many times "restaurants" are mentioned in the complete works of Dickens? Can you think of any?

I bet you’re thinking of pubs, city taverns, country inns, chop houses, coffee houses, wine shops...any restaurants? I only found two instances. Once in Dombey and Son and once in a short story called "The Other Garret" in 1851. Both of these restaurants were in Paris and neither restaurant is described in any detail or even named, as opposed to such Dickensian taverns as the George and Vulture or the Maypole Inn.

Restaurants were actually a new idea at the beginning of the 19th century. Before restaurants, and this goes back to antiquity, if you didn’t eat at home you relied on taverns or inns for your meals. And there you were served with whatever the proprietor had gotten from the neighboring farms that day. You had no choice of dishes.

If you were staying at an inn, you paid a set fee for your lodgings and your meals, and you probably ate at a scheduled time and probably sat with strangers, sharing whatever food was placed on the tables. This usually meant that everyone ate very quickly. And everyone paid the same price, whether you had a large meal or a small one, depending either on your appetite or the quickness of your hands and mouth. The locals wouldn’t want to eat there.

Taverns were more interested in selling ale, beer, and other spirits than food, and so they also had a very limited choice of food.

Of course, there were also vendors on the streets selling oysters, shrimps, pineapples, oranges, calling out, "Two a Pinny," or perhaps, "pertaters, kearots and turnups." That song in the musical, Oliver! is actually rather accurate. Nuts, muffins, crumpets and rock-candy were sold from stalls, wheeled stands or even trays. You could buy a glass of almost anything but alcohol on the street – ginger-beer, sassafras tea, curds and whey, coffee, milk; but not good old plain, safe drinking water. This was the world that Dickens loved to write about.

The first restaurant recorded in the Western World, that was in the form of what we think of as a restaurant, where the emphasis was on selling food, was a Parisian establishment in 1782. It sold a soup made out of sheep feet and a white sauce – which would have been nourishing and inexpensive. The word for this concoction was "restaurant" which meant in 18th century French, "food that restores." The word soon changed from meaning "what was sold" to "where it was sold."

The French Revolution helped the idea of restaurants to spread as chefs and cooks for the aristocracy lost their positions and displaced people from all over needed sustenance as they traveled throughout the country. The new French importation, the restaurant, then spread to England and to the USA.

Jullien's Restrator in Boston was the first restaurant in the US, opening in 1794, but it still had a shared meal placed on a communal table with customers helping themselves.

The first restaurant that used the concept of each customer being served individually, at their own tables, with the specific food he or she ordered from a menu and arranged on a plate, was Delmonico's in New York City in 1830.

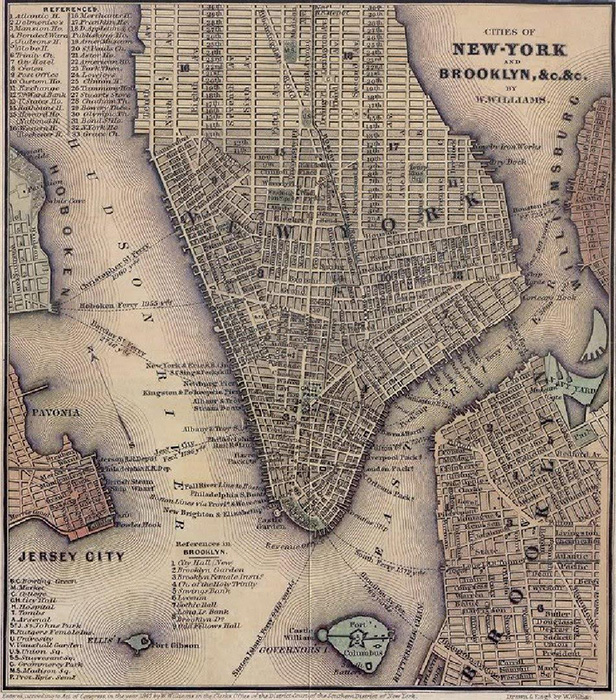

NEW YORK CITY - 1830

SOUTH WILLIAM, WILLIAM AND BEAVER STREETS ARE AT THE RIGHT SIDE OF THE TRIANGULAR PLOT OF LAND NEAR THE BOTTOM OF MANHATTAN

A Swiss-born sea captain, Giovanni Del Monico, (two parts to the last name) often traded in the mile long strip of civilization at the southern end of Manhattan. Giovanni realized that the European residents, mostly agents of export houses, might like something more civilized than the ubiquitous taverns that were scattered around town. He brought in his brother Pietro, who was a confectioner and in 1827 they opened a small café, selling coffee, wine and, of course, sweets and pastries. There were six tables and a few chairs. Three years later they expanded their menu to incorporate some of the ideas of that recent French development – the restaurant.

They anglicized their names to John and Peter Delmonico and opened the first restaurant to offer a leisurely lunch and dinner.

Delmonico's offered only the highest quality foods prepared with the most delicious recipes. They did not worry if the food had to be highly priced...as long as it was of the highest quality.

They offered the finest wines and served their food on fine china, and on (for the first time in America) – tablecloths. Their guests sat at their own tables – not with strangers. The staff was always professionally courteous. They also had the first printed menu and an extensive selection of food.

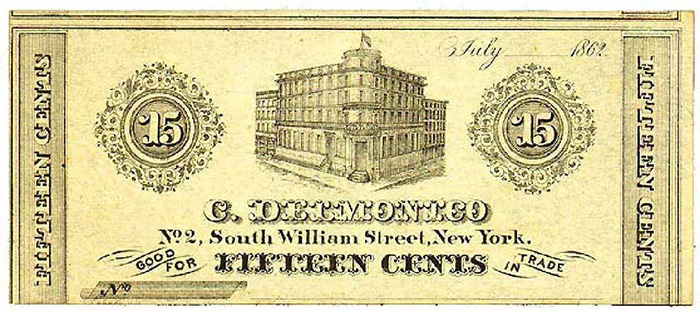

SPECIAL PROMOTIONAL MONEY FOR THE SOUTH WILLIAM AND BEAVER STREETS RESTAURANT

In 1836, they bought a plot of land at the corner of William, South William and Beaver Streets and erected the first building that was designed to be a restaurant. This building was 3½ stories high, with an entrance on the corner that featured two marble Corinthian columns from the ruins of Pompeii. There were large dining rooms called saloons, private dining rooms and 16,000 bottles of imported French wine in the cellar.

With this building the brothers for the first time officially called their establishment "Delmonico’s Restaurant."

The public called the building "The Citadel."

Think about what they achieved without modern technology.

There were no refrigerators or canned goods; everything had to be in season and fresh.

The brothers bought a 220 acre farm on Long Island in 1834. There they could grow vegetables for their restaurant. They also had to have their sources for livestock nearby, as well as cows for milk, cream and cheese.

The kitchen was on the third floor – you wouldn’t want your guests to have to climb stairs in those pre-elevator days.

There was no gas at the start of the century so everything was cooked with wood or coal. Dining at night would be by candlelight. Of course, by the time of the Dickens Press Dinner gas would be available for illumination and cooking.

Over the years their chefs introduced some classic dishes to the world: Oysters Rockefeller, Baked Alaska, Eggs Benedict, Chicken à la King, Delmonico steaks, Delmonico potatoes, Hamburg Steak...later called Hamburger, and Lobster Wenberg.

Lobster Wenberg was named by the renowned chef, Charles Renhofer after a friend of his, a shipping magnate named Ben Wenberg. But they had a falling out so the chef reversed the first three letters of his former friend’s name and it became Lobster Newberg.

Delmonico Steak was item 86 on the menu and when it sold out the wait-staff would say that it was 86'd.

Other Delmonico firsts include:

The first printed menu and a separate wine menu.

They were the first restaurant that allowed women to eat in the dining room alone or as a group.

Delmonico’s was the first restaurant to hire women for front-of-the-house duties, usually as cashiers.

And they were the first restaurant to distinguish between waiter and busboy duties.

Regular diners included Jenny Lind (who reportedly ate there after every show), J.P. Morgan, and Lillian Russell (usually in the company of Diamond Jim Brady). Other guests included Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, William Astor, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Nikola Tesla. Harry K. Thaw, when he was imprisoned in the Tombs during his murder trial, had all his meals sent over from Delmonico's. It is said that every president from Andrew Jackson to Teddy Roosevelt dined there. Table seatings were done on a first come – first served basis, no matter how rich and famous you were. The newspapers delighted in reporting public figures who were seen standing in the waiting line.

The brothers brought in their nephew Lorenzo to help run the business and he eventually took over with equal enthusiasm and expertise.

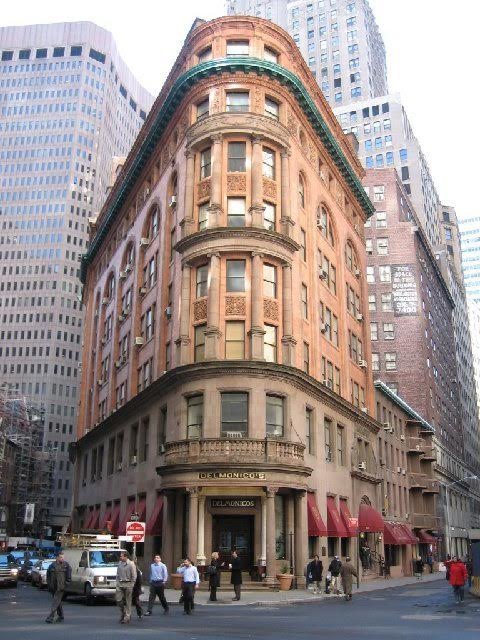

SOUTH WILLIAM AND BEAVER STREETS TODAY

Lorenzo observed how New York was growing north and he followed the city’s growth with new Delmonicos. Over the years Delmonico's opened at nine locations and rebuilt the Beaver Street location in 1891.

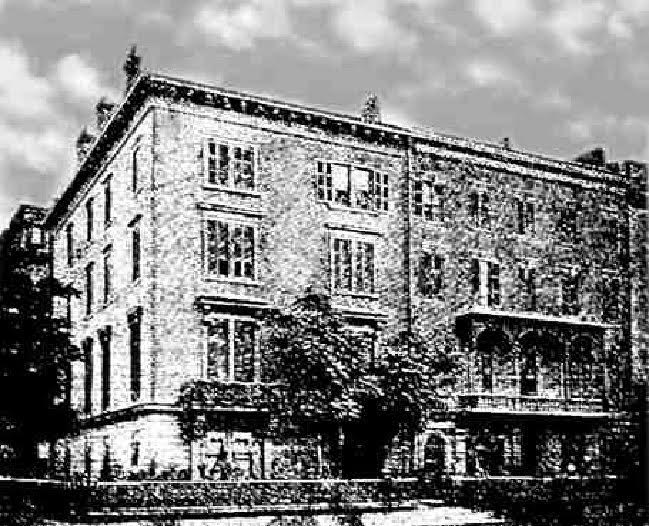

DELMONICO'S, FIFTH AVE AND 14TH STREET

Lorenzo converted a mansion at the northwest corner of 14th Street and Fifth Avenue, across Fifth Avenue from Union Square, into the most luxurious restaurant that New York had ever seen. We want to pay special attention to this location for it was here that the Dickens Press Dinner took place. It opened in April of 1862. The New York Tribune reported:

"As New York spreads herself, so must the House of Delmonico dilate. Before Fifth Avenue was built, there was the downtown Delmonico; when it was achieved, there were the Chambers Street and Broadway Delmonicos; and now that Central Park is undertaken, precedent to a line of noble mansions to its walls, Delmonico has spread up to the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fourteenth Street . . ."

"The service is splendid. The waiters noiseless as images in a vision -- no hurry-scurry or preparation. The dishes succeed each other with a fidelity and beauty like the well composed tones of a painting or a symphony. It was a brilliant overture to the noble operate henceforth to be played there."

Delmonico's in its various locations flourished for almost a century but in 1919 it all came to an end.

Prohibition.

There was no wine in the famed wine cellar and many of the traditional dishes needed wine or spirits for their recipe.

A few years after prohibition was repealed some businessmen opened up restaurants called Delmonico’s. One was in the building at the corner of South William and Beaver Streets – which had been rebuilt in 1891 to be 8 stories high. The Delmonico family sued to prevent the use of their name but the court decided that since they had abandoned the business, and the word Delmonico had by now come to mean high quality, they could not prevent others from using the name. So if you dine at Delmonico's on Beaver Street today, it is in a Delmonico's building, but that is the only connection to the Delmonico's of the past. The ZAGAT Guide said that they spend more effort with the decor than the food. The columns from Pompeii are still there.

But lets go back to 1868. The New York Press Club had written to Dickens and asked him if he could attend a banquet in his honor. The only date he had free was April 18th and that was quickly agreed upon. The members of the local press were invited and told not to report on the event prior to its occurrence. But word did leak out and people from all over were clamoring for tickets. About two hundred tickets were sold at $15 each. The organizers considered switching to a larger venue to accommodate a larger crowd but eventually decided to stay with their original plan.

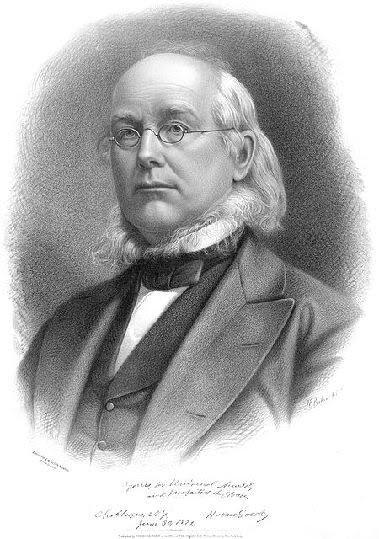

Dickens was staying at the Westminster Hotel, a short walk across Union Square, at 16th Street and Irving Place. But Dickens was not feeling well that evening and it was touch and go for a while whether he could muster up the strength for the short journey and the long evening. Messengers were sent back and forth between Delmonico’s and the hotel with inquiries about his condition and bulletins reporting his progress. Dickens's doctor was called in and he applied lotions and adroitly bandaged Dickens’s foot and leg and, although an hour late, Dickens finally entered the private banquet room leaning on Horace Greeley.

HORACE GREELEY - EDITOR OF THE NEW YORK TRIBUNE

Plenty of newspapers reported on the event – there were almost two hundred newspapermen there, after all, so we know pretty much what happened.

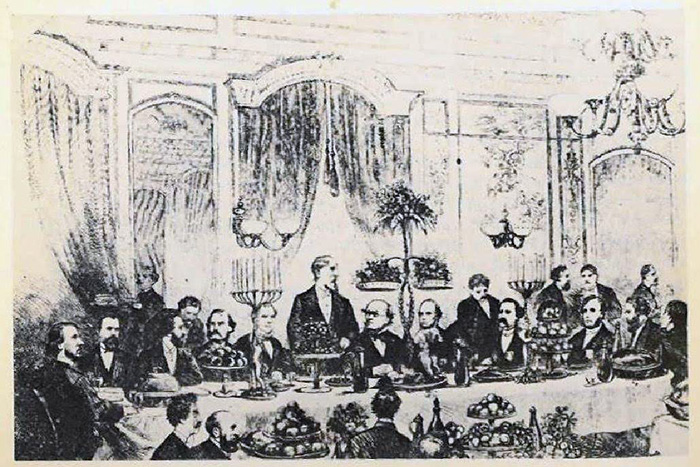

Scene: A large Dining Room in Delmonico’s. 5 PM, April 18, 1868. American Flags and Union Jacks decorate the room. The room is lit by gas.

The New York Tribune: "The decoration of the tables and the room was in exceedingly good taste and the rare flowers that graced the board filled the room with the genial breath of spring."

And, of course...NO LADIES! Men only!

Actually at a later date, Horace Greeley refused to preside over a meeting of the New York press club unless female members of the press could attend. But they were barred from the Dickens affair and that set off such resentment that several women-only clubs were founded in America.

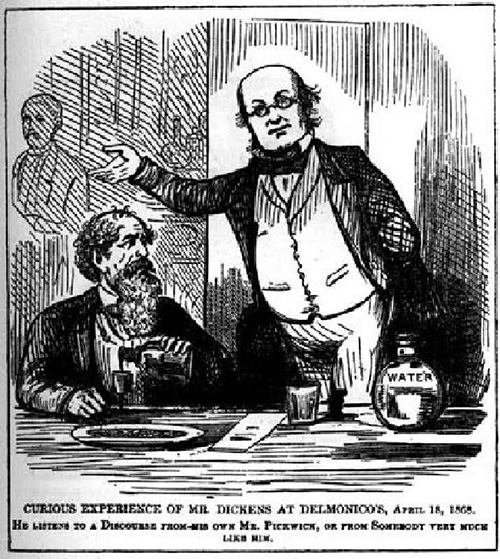

There are eight large tables seating 204 gentlemen. That's about 25 per table. Philadelphia was represented by some gentlemen from the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Ledger as well as publisher, J.D. Lippincott. At 6 p.m. Charles Dickens entered leaning on Horace Greeley – and made for the head table. Thomas Nast was seated in front of the head table and preserved the dinner with a well-known sketch. (below)

"A fine band of music was in attendance in an adjoining room and played choice selections and the national airs of the two countries of the distinguished guest and his entertainers."

While the band was playing, "My Country, Tis of Thee," nobody talked. Delmonico's was the first restaurant that allowed people to talk while the band played but that is years in the future.

The Tribune: "The bill of fare was excellent, and by an ingenious nomenclature the different dishes were made to compliment some well-known personages in the walks of literature."

Edgar Johnson writes in his biography of Dickens:

"The staggering affair progressed through course after course in which the diners had choices of at least three dozen elaborate dishes, including such items as 'Crème d’asperges à la Dumas,' 'Timbales à la Dickens,' ... 'Coutelettes la Fenimore Cooper,' ... and 'Soupirs a la Mantalini.'" The confectionary triumphs of the pastry cooks included a "temple de la Litterature; trophees à l'auteur; Stars and Stripes; ... monument de Washington; and colonne triumphale."

The New York World reported, "Sairey Gamp, Betsy Prig, and Poor Joe and Captain CuttIe blossomed out of charlotte russe, and Tiny Tim was discovered in pate de foie gras."

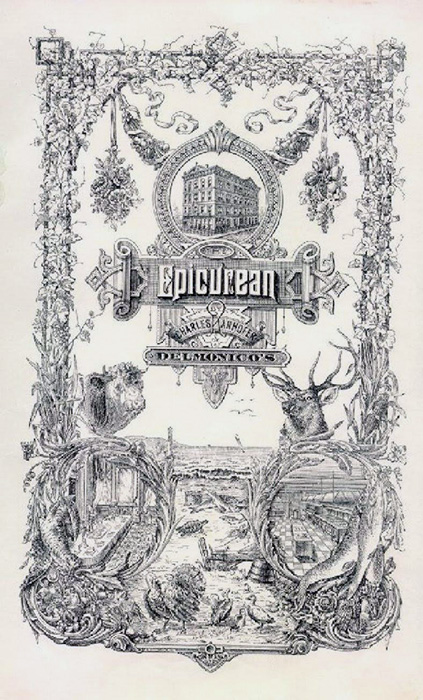

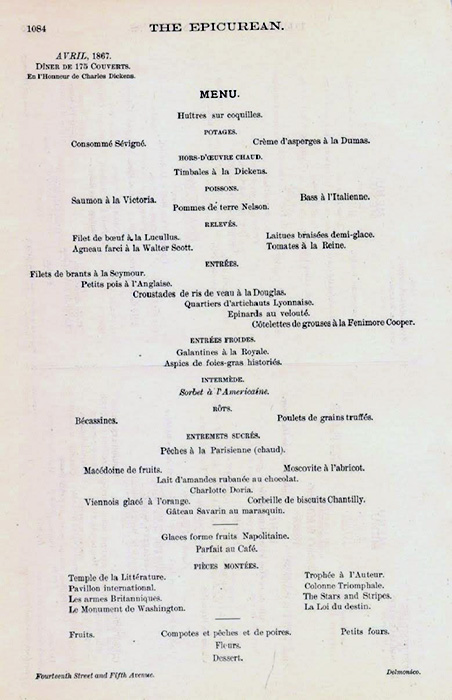

This menu comes from Chef Ranhofer's book, The Epicurean, published in 1894. http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/cookbooks/html/books/book-47.cfm

Note that it does not match the newspaper reports of 1868, and gives the date of the Press Dinner as April, 1867. Elsewhere in The Epicurean, Ranhofer talks about "Veal pie à la Dickens" and "Beet fritters à la Dickens," named in honor of Dickens's visit to New York. These two dishes do not appear in Ranhofer's copy of the menu (above) for the Press Dinner, but Ranhofer elsewhere publishes recipes for the two dishes above and another dish - Beetroot Fritters a la Dickens.

Around 9 PM ...(what a long evening)…Horace Greeley "arose amid loud applause and upon the restoration of silence, said..."

SPEECH OF MR. GREELEY

"Gentlemen of the American Press:-- It is now a little more than twenty-four years since I, a young printer, recently located in the City of New York, had the audacity to undertake the editing and publishing a weekly newspaper for the first time. Looking around at that day for materials with which to make an engaging appearance before the public, among the London magazines which I purchased for the occasion was The Old Monthly, containing a story by a then unknown writer-known to us only by the quaint designation of 'Boz.' (Great applause.) That story, entitled, 'Mr. Watkins Tottle,' I selected and published in the first number of the first journal with which my name was connected." (Applause.)

"Pickwick was then an uncomical, if not uncreated character. (Laughter.) Sam Weller had not yet arisen to increase the mirth of the Anglo-Saxon race. (Cheers.) We had not heard as we have since heard of the writer of those sketches, whose career then I may claim to have in some sort commenced with my own-(great laughter); and the relation of admirer and admired has continued from that day to the present." (Applause.)

"Friends and fellow-labourers, we honour ourselves tonight in honouring the most successful, the most thoroughly successful, literary man of our time. (Applause.) A man who, we may say, is not ashamed of having come up, as most of us have come up, from the lower rounds of the ladder of the Press, and though none of us have reached such a height as he has, still, I say his success is a sign of hope and encouragement to everyone of us. We are successful in his triumph."

Greeley continued with his favorite theme – everyone can go higher, using Dickens as a prime example.

Greeley: "I will, without further prelude, ask you to join me in this sentiment: "Health and happiness, honour and generous, because just, recompense to our friend and guest, Charles Dickens." (Tremendous applause and three hearty cheers for Charles Dickens.)

RESPONSE OF MR. DICKENS

For the complete speech, click here... http://www.dickens-online.info/speeches-literary-and-social-page83.html

"Gentlemen, I cannot do better than take my cue from your distinguished president, and refer in my first remarks to his remarks in connection with the old natural association between you and me. When I received an invitation from a private association of working members of the Press of New York to dine with them to-day, I accepted that compliment in grateful remembrance of a calling that was once my own, and in loyal sympathy for the brotherhood which, in the spirit, I have never quitted. ('Good, good' and applause.) To the wholesome training of severe newspaper work when I was a very young man I constantly refer my first successes; and my sons will hereafter testify of their father that he was always steadily proud of that ladder by which he rose. (Great applause.) If it were otherwise, I should have but a very poor opinion of their father, which, perhaps, upon the whole, I have not. (Laughter and cheers.) Hence, gentlemen, under any circumstances, this company would have been exceptionally interesting and gratifying to me."

Dickens commented on the size of the crowd, and that despite his cold, his voice has been heard quite a lot recently in America and he would be content not to speak except…and go...

Dickens: "...were it not a duty with which I henceforth charge myself, not only here, but on every suitable occasion, whatsoever and wheresoever, to express my high and grateful sense of my second reception in America, and to bear my honest testimony to the national generosity and magnanimity. (Great applause.) Also, to declare how astounded I have been by the amazing changes that I have seen around me on every side, changes moral, changes physical, changes in the amount of land subdued and peopled, changes in the rise of vast new cities, changes in the growth of older cities, almost out of recognition, changes in the graces and amenities of life, changes in the Press, without whose advancement no advancement can take place anywhere. (Applause.) Nor am I, believe me, so arrogant as to suppose that in the five-and-twenty years there have been no changes in me, and that I have nothing to learn and no extreme impressions to correct when I was here first." (A voice, "Noble" and applause.)

Dickens said he has read reports that he plans to write a new book on America but he assures the gentlemen he has no such intention.

Dickens: "But what I have intended, what I have resolved upon (and this is the confidence I seek to place in you) is, on my return to England, in my own person, to bear, for the behoof of my countrymen, such testimony to the gigantic changes in this country as I have hinted at to-night. (Immense applause.) Also, to record that wherever I have been, in the smallest places equally with the largest, I have been received with unsurpassable politeness, delicacy, sweet temper, hospitality, consideration, and with unsurpassable respect for the privacy daily enforced upon me by the nature of my avocation here and the state of my health. (Applause.) This testimony, so long as I live, and so long as my descendants have any legal right in my books, I shall cause to be republished as an appendix to every copy of those two books of mine in which I have referred to America. (Tremendous applause.) And this I will do and cause to be done, not in mere love and thankfulness, but because I regard it as an act of plain justice and honour."

("Bravo!" and cheers.)

"Gentlemen, the transition from my own feelings toward and interest in America to those of the mass of my countrymen seems to be a natural one; but whether or no I make it with an express object. I was asked in this very city, about last Christmas-time, whether an American was not at some disadvantage in England as a foreigner. The notion of an American being regarded in England as a foreigner at all, of his ever being thought of or spoken of in that character, was so uncommonly incongruous and absurd to me that my gravity was, for the moment, quite over- powered."

"I assure you that…the Englishman who shall humbly strive, as I hope to do, to be in England as faithful to America as to England herself, has no previous conception to contend against. ("Good, good!") Points of difference there have been, points of difference there are. Points of difference there probably will be between the two great peoples. But broadcast in England is sown the sentiment that these two peoples are essentially one-(great applause) If I know anything of my countrymen-and they give me credit of knowing something-if I know anything of my countrymen, gentlemen, the English heart is stirred by the fluttering of those stars and stripes as it is stirred by no other flag that flies except its own." (Tremendous applause and three cheers).

"Finally, gentlemen, and I say this subject to your correction, I do believe from the great majority of honest minds on both sides there cannot be absent the conviction that it would be better for this globe to be ridden by an earthquake, fired by a comet, overrun by an iceberg, and abandoned to the Arctic fox and bear, than that it should present the spectacle of those two great nations, each of whom has, in its own way and hour, striven so hard and successfully for freedom, ever again being arrayed the one against the other. (Tumultuous applause, the company rising to its feet and greeting the sentiment with enthusiasm.) Gentlemen, I cannot thank your president enough, or you enough, for your kind reception of my health and of my poor remarks, but believe me, I do thank you with the utmost fervour of which my soul is capable." (Great applause.)

The band then played "God Save the Queen," the company joining in with enthusiastic voices.

God save our gracious Queen

Long live our noble Queen,

God save the Queen:

Send her victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us:

God save the Queen.

The evening continued with many more speeches, all praising Dickens, but the Inimitable, because of his illness, was long gone.