The Charles Dickens Page

Charles Dickens'

Edwin Drood

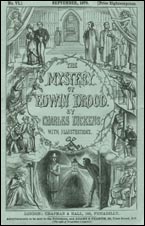

The Mystery of Edwin Drood

The Mystery of Edwin Drood - Published in monthly parts Apr 1870 - Sep 1870

Illustrations | Locations | Plot | Characters | More | Shop for the Book | Shop for the Video

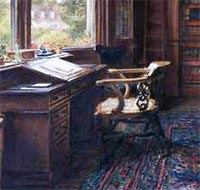

The Empty Chair - by Luke Fildes

Charles Dickens' fifteenth novel, illustrated by Luke Fildes, was his last and was never completed. The story is a murder mystery in which Edwin Drood is supposedly murdered and suspicion is cast on his uncle. Dickens left exactly half of the monthly installments unfinished when, after a day of working on the completion of chapter 22, he suffered a stroke on June 8, 1870 and died the next day.

Although early in planning the novel Dickens told his friend John Forster that he had an idea for a novel in which a nephew would be murdered by his uncle (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 452), Dickens guarded the mystery very closely while writing the story. Much conjecture about the actual outcome of the novel has taken place and The Mystery of Edwin Drood remains a mystery to this day.

Plot

(contains spoilers)

The story is set in the Cathedral town of Cloisterham. Edwin Drood and Rosa Bud, both orphaned, had been promised to each other in marriage by their parents. Their attachment, made in early childhood, has cooled as they are reaching adulthood.

Edwin's uncle and guardian, John Jasper, choirmaster and opium addict, is Rosa's music teacher and is secretly in love with her.

Helena and Neville Landless, orphans from Ceylon, are brought to Cloisterham by their guardian, the pompous Luke Honeythunder, Neville to be tutored by the Cathedral's Minor Canon, Septimus Crisparkle, and Helena is housed at the Nun's House where Rosa lives, run by Miss Twinkleton.

Neville is attracted to Rosa and quarrels with Edwin over his indifferent treatment of his future wife. The quarrel later turns violent at Jasper's residence, fueled in part by strong drink supplied by Jasper. A reconciliation is sought by Reverend Crisparkle and the two agree to meet at Jasper's on Christmas Eve.

Drood meets with Rosa's guardian, Hiram Grewgious, at his chambers at Staple Inn in London. Grewgious gives Drood a ring, taken from the finger of Rosa's dead mother, with instructions to give the ring to Rosa on the date of their betrothal, and cautions him that if he has doubts of his love for Rosa that he will return the ring to Grewgious.

Drood journeys to Cloisterham from London for Christmas and meets with Rosa. They mutually agree to end their relationship as lovers and cancel their marriage plans. They also agree not to tell Jasper of their decision as Drood feels the cancellation of their impending marriage will be a shock to his uncle. They agree that Grewgious will inform Jasper of their decision.

Jasper goes with Durdles, the sexton, on a mysterious tour of the Cathedral. Durdles has the ability to tap on the tombs and determine the contents and Jasper, plying Durdles with liquor as they go, is interested in this ability.

On Christmas Eve Neville plans for a two week walking tour during the holidays. That evening Neville and Edwin meet at Jasper's for the reconciliation as a terrible storm hits the area. The two leave together to walk down to the river to observe the effect of the storm.

Next morning, Christmas Day, as the townspeople observe the damage done by the storm, Jasper informs them that Edward Drood is missing. Suspicion is cast upon Neville and he, having left early in the morning on his walking tour, is brought back to town by a group of townspeople.

Neville angrily declares his innocence and, lacking hard evidence, is released by Mayor Sapsea to Reverend Crisparkle. Foul play in Drood's disappearance is confirmed when Crisparkle finds Drood's watch and shirt-pin in the river. Grewgious informs Jasper of Edwin and Rosa's decision to break off their engagement and Jasper is deeply upset. Jasper vows to find the killer of his nephew.

Six months pass and Neville, shunned by the town, has been spirited away to London by Crisparkle in chambers near Grewgious in Staple Inn. He befriends a neighbor, Mr Tartar, a former member of the Royal Navy and old friend of Crisparkle. Grewgious spots Jasper lurking nearby apparently watching Neville.

Back in Cloisterham, Jasper meets Rosa, declares his love for her, and swears revenge against Neville for the death of Edwin. Rosa, terrified of Jasper, flees to London and confides her fears to Grewgious. Grewgious finds her lodging with Mrs Billickin. Miss Twinkleton comes to London as Rosa's chaperone and Helena comes to live with Neville.

A mysterious visitor appears in Cloisterham, Dick Datchery, a man of indeterminate age with an unusually thick shock of white hair and a military bearing. He seems to take covert interest in John Jasper and takes lodging near Jasper's. He hires the boy, Deputy, to watch Jasper and keeps a log of his findings in chalk on his cupboard.

Jasper, meanwhile, has visited Puffer, the opium woman in London and in an opium trance he relates information of a strange, metaphorical journey that he has taken many times. Puffer listens attentively to these revelations and, hearing that Jasper will go back to Cloisterham that evening, goes there before him where she meets Datchery and finds out that Jasper sings in the Cathedral. Next morning Datchery observes her there watching Jasper.

...at this point the novel suddenly stops.

Complete List of Characters:

Character descriptions contain spoilers

The Mystery of Edwin Drood Links:

Luke Fildes - Illustrator for Edwin Drood

Wikipedia

Bazzard is Datchery - The Dickensian 1908

Make your own case at The Drood Inquiry

Edwin Drood

Further Information

Edwin Drood - The Last Page

See a facsimile of the last page written by Dickens on the afternoon of June 8, 1870.

Possible Solutions

Possible solutions to The Mystery of Edwin Drood began to appear almost as soon as Dickens' death was announced. Despite Dickens' friend and biographer, John Forster, reporting that the author had told him early on that he had an idea for a new book where a nephew would be murdered by his uncle (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 452), many of the initial solutionist's theories centered on Drood being alive and in hiding (Schlicke, 1999, p. 389).

Possible solutions to The Mystery of Edwin Drood began to appear almost as soon as Dickens' death was announced. Despite Dickens' friend and biographer, John Forster, reporting that the author had told him early on that he had an idea for a new book where a nephew would be murdered by his uncle (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 452), many of the initial solutionist's theories centered on Drood being alive and in hiding (Schlicke, 1999, p. 389).

Attention was focused on the book's cover design, initially worked up by Dickens' son-in-law Charles Collins and redesigned by artist Luke Fildes, for clues as to the end of the mystery. Dickens had worked closely with his artists on the covers for the monthly parts of his works, foreshadowing events that would take place in the novels without really giving anything away. Nothing conclusive could be discerned from the Drood cover although later Fildes reported that Dickens had told him that Drood's uncle would strangle his nephew with his necktie (Orford, 2018, p. 71-72).

In addition to the Edwin Drood being dead or alive debate, Droodists also argue their cases for the identity of Datchery, a mysterious character who appears near the end of the unfinished novel and of whom Dickens leaves us with the distinct impression of being someone in disguise. On this point Forster makes no mention.

Possible solutions to the book continue to this day in books such as Felix Aylmer's The Drood case (1965) and John Thacker's Edwin Drood: Antichrist in the Cathedral (Critical Studies Series) (1990). Modern solutionist lean toward the guilt of Jasper who is experiencing some sort of split personality disorder (Schlicke, 1999, p. 395).

In his 2018 book, The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Charles Dickens' Unfinished Novel and Our Endless Attempts to End It, Pete Orford explores the history of possible conclusions, rewrites, and stage/film productions. You can also visit his Website, The Drood Inquiry, to submit your own thoughts on possible conclusions.

Queen Victoria

While writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood Charles Dickens had a private interview with Queen Victoria on March 9, 1870, less than three months before his death. Dickens, in a letter to the Queen's advisor, Arthur Helps, and enclosing the first monthly number of Edwin Drood, asked him to tell the Queen that if she were interested to know a little more of the mystery in advance of her subjects he would be happy to divulge his plans (Hartley, 2012, p. 434-435). The Queen never took him up on the offer (Wilson, 1974, p. 28).

While writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood Charles Dickens had a private interview with Queen Victoria on March 9, 1870, less than three months before his death. Dickens, in a letter to the Queen's advisor, Arthur Helps, and enclosing the first monthly number of Edwin Drood, asked him to tell the Queen that if she were interested to know a little more of the mystery in advance of her subjects he would be happy to divulge his plans (Hartley, 2012, p. 434-435). The Queen never took him up on the offer (Wilson, 1974, p. 28).

The Last Chapter

The Last Chapter

by Lyn Squire

An original solution to the Drood mystery.

Opium

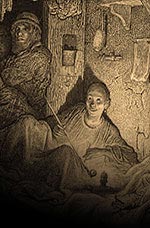

Charles Dickens has John Jasper frequenting an opium den run by a haggard woman, known as the Princess Puffer, who claims that she has the true secret of mixing the opium, as opposed to Jack Chinaman, a competitor on "t'other side of the court" (Edwin Drood, p. 2).

On a visit to London's East End, accompanied by friends, and with a police escort, Dickens visited an opium den run by a haggard old woman smoking a pipe made from an old ink bottle. Dickens later used this woman as the original for Princess Puffer (Slater, 2009, p. 599).

On a visit to London's East End, accompanied by friends, and with a police escort, Dickens visited an opium den run by a haggard old woman smoking a pipe made from an old ink bottle. Dickens later used this woman as the original for Princess Puffer (Slater, 2009, p. 599).

Opium dens were prevalent in many parts of the world in the 19th century, most notably China, Southeast Asia, North America and France. Throughout the West, opium dens were frequented by and associated with the Chinese, because the establishments were usually run by Chinese who supplied the opium as well as prepared it for visiting non-Chinese smokers. Most opium dens kept a supply of opium paraphernalia such as the specialized pipes and lamps that were necessary to smoke the drug. Patrons would recline in order to hold the long opium pipes over oil lamps that would heat the drug until it vaporized, allowing the smoker to inhale the vapors (Wikipedia).

Staple Inn

Doorway to Staple Inn

Staple Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery, dates from the 16th century and remains a fine example of Elizabethan architecture in London (Williams, 1906, p. 1). Mr Grewgious has chambers at Staple Inn and finds Neville Landless rooms here.

Furnival's Inn, another former Inn of Chancery, was adjacent to Staple Inn across Holborn, Charles Dickens lived here from 1834-37. Furnival's Inn was torn down in the late 19th century and on the site now stands the Prudential Assurance Building (Weinreb, 2008, p. 432-433).

By the way, the inscription above the door that mildly concerns Mr Grewgious as he enters his lodging at Staple Inn stood for John Thompson who served two terms as Principal of Staple Inn (Williams, 1906, p. 137).

Dickens' Death

Charles Dickens wished to be buried without pomp in the small graveyard under Rochester Castle wall or in one of the small country churchyards in Cobham or Shorne. These wishes went unheeded as the mourning nation buried him with honor in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 513).

Charles Dickens wished to be buried without pomp in the small graveyard under Rochester Castle wall or in one of the small country churchyards in Cobham or Shorne. These wishes went unheeded as the mourning nation buried him with honor in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 513).

Dickens left an estate valued at £93,000 (Patten, 1978, p. 324-325).

Rochester

Rochester, Kent, which becomes the fictional town of Cloisterham in The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Slater, 2009, p. 605), was well known to Charles Dickens. He spent the happiest days of his childhood here when his father's job at the Navy Pay Office moved the family to Chatham from 1817 to 1823 (Davis, 1999, p. 58). At the time Drood was being written, Dickens lived at Gads Hill Place, two miles outside of Rochester. Dickens also used the area as a setting for parts of Pickwick and Great Expectations.

Rochester, Kent, which becomes the fictional town of Cloisterham in The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Slater, 2009, p. 605), was well known to Charles Dickens. He spent the happiest days of his childhood here when his father's job at the Navy Pay Office moved the family to Chatham from 1817 to 1823 (Davis, 1999, p. 58). At the time Drood was being written, Dickens lived at Gads Hill Place, two miles outside of Rochester. Dickens also used the area as a setting for parts of Pickwick and Great Expectations.

Charles Dickens' life during the serialization of Edwin Drood

Apr 1870 - Sep 1870Dickens' age: 58

April 1870

Dickens is forced by poor health to end the very popular reading tours as the new novel begins publication (Johnson, 1952, p. 1144-1145).

Sales of the early monthly parts were very good, reaching 50,000 per month (Patten, 1978, p. 216).

Death of friend, artist Daniel Maclise (Johnson, 1952, p. 1149).

May 1870

Death of friend, Punch editor Mark Lemon (Johnson, 1952, p. 1149).

June 1870

On June 8th Dickens worked on Edwin Drood at Gads Hill Place, completing the 6th (of a scheduled 12) monthly part (3 months ahead of publication). At dinner that evening he suffered a stroke and died the next day (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 1076-1079).

July 1870

The first of three final monthly parts of the novel are published posthumously (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 521).

September 1870

Publication abruptly stops with exactly half of the novel finished, and the Mystery of Edwin Drood still a mystery (Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 521).