The Charles Dickens Page

Charles Dickens'

The Old Curiosity Shop

The Old Curiosity Shop - A Tale

The Old Curiosity Shop - Published in weekly parts Apr 1840 - Feb 1841

Illustrations | Locations | Characters | More | Shop for the Book | Shop for the Video

Charles Dickens' fourth novel was illustrated by George Cattermole and Phiz, with a single illustration each from Samuel Williams and Daniel Maclise.

This installment novel, published in Master Humphrey's Clock, was so popular that its weekly sales rose to a hundred thousand (Patten, 1978, p. 110).

It tells the story of Nell Trent and her grandfather as they wander the English countryside, northwest of London, trying to evade Daniel Quilp, probably Dickens' most evil villain. Nell's grandfather has borrowed money from Quilp to support a gambling habit and has lost everything, including the curiosity shop.

The tale is richly populated with the interesting and bizarre cast of characters Nell and her grandfather meet along their journey.

As the conclusion of the story neared Nell is exhausted from the travel and lack of food. Dickens was inundated with letters begging him to spare Nell's life (Slater, 2009, p. 158). Dickens confided to George Cattermole, one of the illustrators of the book, that "I am breaking my heart over this story" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 318).

With the final installment arriving by ship, crowds in New York shouted from the pier "Is Little Nell dead?" (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 319)

Complete List of Characters:

Character descriptions contain spoilers

Old Curiosity Shop Links:

The Victorian Web

Bartleby.com

Wikipedia

Herb Moskovitz's excellent article Punch and Dickens

Further Information

The Old Curiosity Shop-Holborn

The Old Curiosity Shop on Portsmouth Street in Holborn, dating from 1567 and said to be constructed from salvaged ship wood, survived both the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the Blitz during World War II. It is erroneously thought to be the inspiration for the shop in the novel although evidence seems to show that the name was changed after the book was published (Charles Dickens Museum).

The Old Curiosity Shop on Portsmouth Street in Holborn, dating from 1567 and said to be constructed from salvaged ship wood, survived both the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the Blitz during World War II. It is erroneously thought to be the inspiration for the shop in the novel although evidence seems to show that the name was changed after the book was published (Charles Dickens Museum).

Master Humphrey's Clock

Dickens began the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop in his weekly miscellany Master Humphrey's Clock the plan being to continue the tale from time to time amidst other articles as the mood took him. The story, however, captured the imagination of both Dickens and his readers and soon took over the entire publication. Dickens, feeling rather cramped within the confines of the Clock, allowed the story to burst out beginning with chapter four (Slater, 2009, p. 152). Thus, at the end of chapter three, he has Master Humphrey, heretofore acting as narrator, inform the readers:

Dickens began the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop in his weekly miscellany Master Humphrey's Clock the plan being to continue the tale from time to time amidst other articles as the mood took him. The story, however, captured the imagination of both Dickens and his readers and soon took over the entire publication. Dickens, feeling rather cramped within the confines of the Clock, allowed the story to burst out beginning with chapter four (Slater, 2009, p. 152). Thus, at the end of chapter three, he has Master Humphrey, heretofore acting as narrator, inform the readers:

And now that I have carried this history so far in my own character and introduced these personages to the reader, I shall for the convenience of the narrative detach myself from its further course, and leave those who have prominent and necessary parts in it to speak and act for themselves (The Old Curiosity Shop, p. 28).

In the original serialization of the novel the grandfather's brother, the single gentleman, turns out to be none other than Master Humphrey himself.

Thomas Moore

Thomas Moore

Thomas MooreCharles Dickens loved to quote or allude to popular songs and poems in his work. These are easy to miss today but would have been easily spotted by Victorian readers. In an article entitled Charles Dickens and Thomas Moore by Donal O'Sullivan (1948) O'Sullivan counts five such poems or songs from Robert Burns alluded to or quoted in Dickens, five from John Gay, and several poets responsible for one or two. But far and away the poet that Dickens quoted the most, with more than thirty, was Irish poet Thomas Moore (1779-1852). Among Dickens' characters who quote Moore none are more prolific than Richard Swiveller from The Old Curiosity Shop.

O'Sullivan gives the following example of Swiveller quoting from Moore's Holy Be the Pilgrim's Sleep:

In chapter 65 Dick Swiveller, recovering from brain fever, is being tenderly nursed by the faithful little Marchioness, who has run away from Sampson Brass's: Having eaten and drunk to Mr. Swiveller's extreme contentment, given him his drink, and put everything in neat order, she wrapped herself in an old coverlet and lay down upon the rug before the fire. Mr. Swiveller was by that time murmuring in his sleep, 'Strew then, oh strew a bed of rushes. Here will we stay, till morning blushes. Good night, Marchioness!' (The Old Curiosity Shop, p. 488)

As a testament to Dickens' love of Thomas Moore, Peter Ackroyd reports in his biography, Dickens, that in order to protect his voice during the 1858 reading tour, Dickens "dosed himself regularly with barley water and mustard poultices" and sang Moore's Irish Melodies as he walked along (Ackroyd, 1990, p. 836).

Pain no longer?

The inspiration for Nell is believed to be Charles Dickens' sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth. Dickens was devoted to his wife's younger sister and when she died suddenly in 1837 at the age of 17 he was devastated. He took a ring from Mary's finger and wore it the rest of his life, he also said that he wanted to be buried in the same grave as Mary.

However, several passages in The Old Curiosity Shop perhaps reveal a coming-to-terms with the loss of Mary three years earlier. In chapter 17 the old woman visiting the grave of her husband who died a young man tells Nell that early in her grief she came there to cry and mourn and hoped to die too but that now it is "pain no longer, but a solemn pleasure" to visit the grave.

In chapter 26, as Nell is visiting the graves of children in the churchyard, the narrator says that she did not sufficiently consider to what a bright and happy existence those who die young are borne, and how in death they lose the pain of seeing others die around them.

In chapter 26, as Nell is visiting the graves of children in the churchyard, the narrator says that she did not sufficiently consider to what a bright and happy existence those who die young are borne, and how in death they lose the pain of seeing others die around them.

In chapter 54, as Nell laments the uncared-for graves in the churchyard, the sexton tells her that at first the graves are tended every day by "tender, loving friends" but later the tending falls to once a week, then once a month, and later not at all. As Nell says she grieves to hear it, the old man says that on the contrary, he takes it as a good sign for the happiness of the living.

Later in chapter 54 Nell is speaking with the schoolmaster in the neglected churchyard and says she "grieves to think that those who die about us are so soon forgotten" he tells her that the unvisited graves are the inspiration of good actions and good thoughts of those who remember the dead and have chosen to go on living.

Deathbed of Little Nell

Charles Dickens' instructions to George Cattermole for the illustration The Death-Bed of Little Nell:

The Deathbed of Little Nell by George Cattermole

"The child lying dead in the little sleeping room, which is behind the open screen. It is winter-time, so there are no flowers; but upon her breast and pillow, and about her bed, there may be strips of holly and berries, and such free green things. Window overgrown with ivy. The little boy who had that talk with her about angels may be by the bedside, if you like it so; but I think it will be quieter and more peaceful if she is alone. I want it to express the most beautiful repose and tranquility, and to have something of a happy look, if death can...I am breaking my heart over this story, and cannot bear to finish it" (Letters, 1969, v. 2, p. 171-172).

The Advertising Jingles of Mr Slum

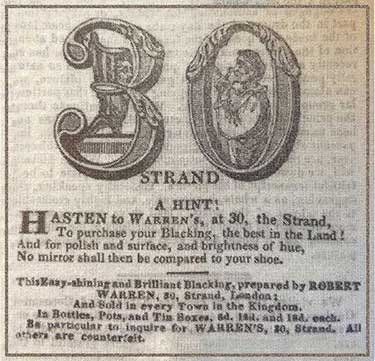

When John Dickens was imprisoned for debt in the Marshalsea debtors' prison his 11-year-old son Charles was sent to work at Warren's Blacking Factory at Hungerford Stairs, washing and glueing labels on pots of boot blacking, to help support the family. Dickens never mentioned this traumatic period of his childhood to anyone during his lifetime except for his friend, and future biographer, John Forster who revealed it after Dickens' death (Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 22-39). Dickens, however, did manage to weave the blacking experience into his fiction, and Warren's Blacking is mentioned, and alluded to, multiple times in his works.

Robert Warren, owner of one branch of the business, was famous for placing rather bad verse in the advertisements for his product. According to Forster Dickens based the character of Mr Slum, the advertisement jingle writer for Mrs Jarley's Waxwork in The Old Curiosity Shop, on the writer of such jingles for Robert Warren (Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 39). It is even supposed that Dickens himself, when he was a young journalist, wrote some of the advertisement poems for Warren's Blacking (Slater, 2009, p. 36).

Journey's End

In describing the journey Nell and her grandfather take through the English countryside Dickens creates a dream landscape in which no place names are used. The village where Nell dies is thought to be Tong, Shropshire, a place Dickens had visited. A wreath is still placed every year outside St. Bartholomew's church at the supposed grave of Little Nell.

BBC - Verger in Tong faked grave of Dickens' Little Nell

Mapping Little Nell's Journey

Explore a map of the probable route along with some evidence to support it.

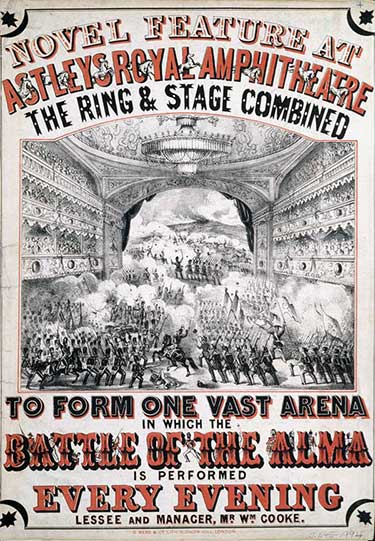

Astley's Theatre

Kit takes his mother to Astley's theatre on the Surry side of the Thames on Westminster Bridge Road. Astley's mixed theatre with circus including equestrian performances. Philip Astley, who opened the amphitheatre in 1794 after his original tent structure of 1769 burned down, is considered a pioneer of the modern circus. After being rebuilt several times the structure was demolished in 1893 (Weinreb et al, 2008, p. 30).

My Mother

One of the quotations used by the loquacious Dick Swiveller, in this case referring to Kit's mother, is "Who ran to catch me when I fell, and kissed the place to make it well? My Mother" (The Old Curiosity Shop, p. 289).

One of the quotations used by the loquacious Dick Swiveller, in this case referring to Kit's mother, is "Who ran to catch me when I fell, and kissed the place to make it well? My Mother" (The Old Curiosity Shop, p. 289).

This is from the popular poem My Mother by Ann Taylor (1782-1866). Ann's sister Jane (1783-1824) wrote Twinkle Twinkle Little Star.

My Mother

Who fed me from her gentle breast,

And hushed me in her arms to rest,

And on my cheek sweet kisses prest?

My Mother.

When pain and sickness made me cry,

Who gazed upon my heavy eye,

And wept, for fear that I should die?

My Mother.

Who dressed my doll in clothes so gay,

And fondly taught me how to play,

And minded all I had to say?

My Mother.

Who ran to help me when I fell,

And would some pretty story tell,

Or kiss the place to make it well?

My Mother.

And can I ever cease to be

Affectionate and kind to thee,

Who was so very kind to me?

My Mother.

- Ann Taylor

The Curiosity Shop-Dickens' Description

One of those receptacles for old and curious things which seem to crouch in odd corners of this town and to hide their musty treasures from the public eye in jealousy and distrust. There were suits of mail standing like ghosts in armour here and there, fantastic carvings brought from monkish cloisters, rusty weapons of various kinds, distorted figures in china and wood and iron and ivory: tapestry and strange furniture that might have been designed in dreams (The Old Curiosity Shop, p. 4-5).

Punch and Judy

Charles Dickens' fascination with the theatre and his firm belief that the lower classes must have their amusements lead to a love of Punch and Judy shows. This familiar street entertainment finds it way into

The Old Curiosity Shop by way of Codlin and Short, a traveling Punch show that Nell and her grandfather meet on their travels.

Charles Dickens' fascination with the theatre and his firm belief that the lower classes must have their amusements lead to a love of Punch and Judy shows. This familiar street entertainment finds it way into

The Old Curiosity Shop by way of Codlin and Short, a traveling Punch show that Nell and her grandfather meet on their travels.

Herb Moskovitz's excellent article Punch and Dickens.

Charles Dickens' life during the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop

Apr 1840 - Feb 1841Dickens' age: 28-29

April 1840

July 1840

Travels by train to Devon to visit his parents in the house he bought for them principally to get his father out of London, where his constant borrowing was an embarrassment to Dickens (Slater, 2009, p. 155).

August 1840

Visits Bevis Marks, in the city, to look for a house for Sampson Brass, a character in The Old Curiosity Shop (Letters, 1969, v. 2, p. 118).

January 1841

Begins again writing Barnaby Rudge, which he started and then gave up, in January 1839 (Schlicke, 1999, p. 29).

February 1841

Son Walter Savage Landor Dickens born (Slater, 2009, p. 162).

The Old Curiosity Shop (2007)

Sophie Vavasseur, Derek Jacobi