Dickens in America > Dickens Statue in Philadelphia

The Charles Dickens Page

Charles Dickens' and Little Nell

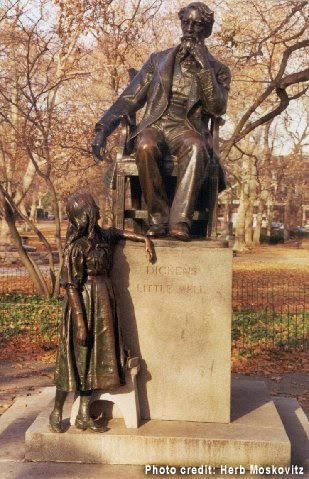

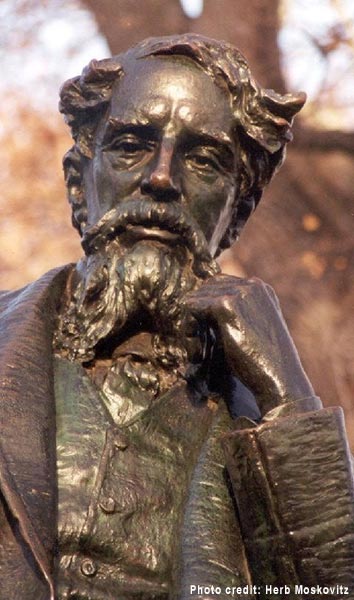

The Statue in Clark Park, Philadelphia by Frank Elwell

By Herb Moskovitz

Reprinted with permission of the author

Published on this site September 13, 2020

Francis Edwin Elwell was born in June of 1858 in Concord, Massachusetts. His parents were dead by the time he was four and he was raised by his grandfather who was a friend of Emerson, Alcott, and Thoreau. Louisa M. Alcott took the place of a mother. Her sister Miss May Alcott ran an art class in Concord and young Frank learned the basics of art from her.

He went on to study at the Ecole des Beaux Artes in Paris and quickly became a highly regarded sculptor.

Examples of Frank Elwell's Other Works

General Winfield Scott Hancock - Gettysburg

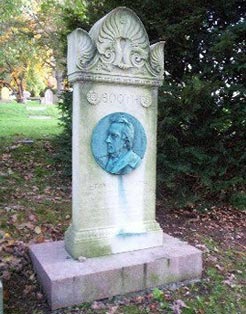

Memorial to Edwin Booth Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge

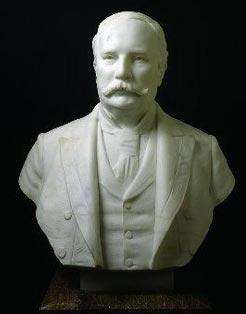

Levi P. Morton (1891), VP under B. Harrison in the capitol.

In the 1880s, Stilson Hutchins, best known as the founder of The Washington Post, commissioned Elwell to create a statue of Dickens to be placed in London.

Little Nell

Theodore Dreiser wrote a sketch about Frank Elwell in the December 1898 New York Times:

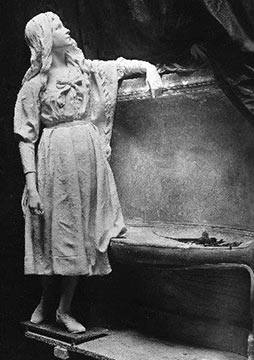

Of all his work, none has evoked more admiration than his statue of Dickens's 'Little Nell' ...This...is a slip of a girl, simply clad, with a face which is innocence and sweetness personified.

When the statue was in preparation, I am told, there came a period when it seemed almost impossible for the artist to continue his work. He had been unable to find a face from which to draw his inspiration-one that should convey the tenderness, patience, and love of the famous original. The sculptor calmly put the thing aside as a subject which might wait forever, if no inspiration offered and went about other affairs. It was all solved for him by a concert, however, where in the face of one of the child singers he found the exact something he desired. He gazed steadily at the little girl, and then made his way quickly back to the studio, where the neglected work was hauled into light and completed.

"Did the child ever see it?" I asked him.

"No, I invited the father," he answered, "and he was planning to come the Monday it was done, but he died just the Saturday before."

Statue signed by F. Edwin Elwell

The statue was completed in 1890 and won a gold medal at the Philadelphia Art Club in 1891, and later won two gold medals at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. When Hutchins did not continue to fund the statue, (Hutchins went mad – which might have had something to do with it) Elwell began to look for other buyers.

Apparently it was sent to England but Dickens’s will specified he wanted to be remembered by his countrymen by his works and did not want any monument, memorial or testimony. When Dickens’s son, Henry Fielding Dickens publicized this, the British people declined the offer and it was sent to Philadelphia for storage.

Fairmount Park officials began negotiating for the piece in 1896 and by 1900 the purchase was completed, and it was installed in Clark Park in 1901.

Information from the Dickens Fellowship

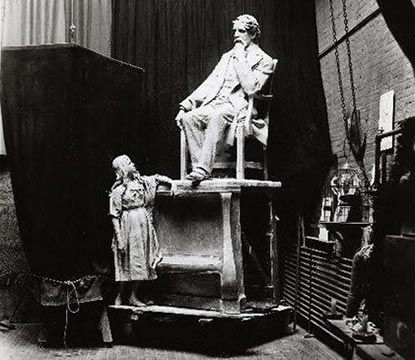

In the archives of the Philadelphia Dickens Fellowship were these photographs showing the creation of the sculpture in Frank Elwell’s studio in lower Manhattan.

Now we know that Elwell took his inspiration from the mysterious girl at the concert, but now we have photos of a young girl posing for Little Nell. Who is she? For a hundred years no one in the Dickens Fellowship or Clark Park knew. But a few months ago a Mr Loeser from Connecticut contacted the Fellowship. He said: "There has been handed down in my family the story that my grandmother nee Florence Lucia Pomero, who was born on 8/4/1877 of Eliza Reynolds and Paulo Pomero in London, England, posed for the figure of 'Little Nell' in the famous Dickens statue in Philadelphia. If this is true the family would feel most honored."

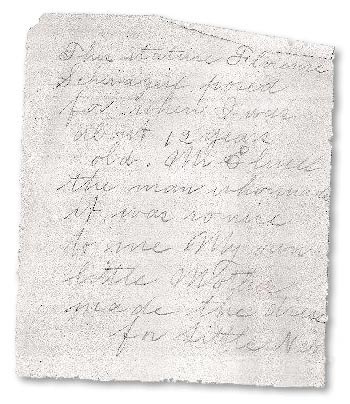

Mr Loeser also sent an attached facsimile of a note written by Mr Loeser's grandmother, apparently confirming the family's belief.

Letter written by Florence Lucia Schwagerl (nee Pomero)

"This statue Florence Schwagerl posed for when I was about 12 years old. Mr Elwell, the man who made it, was so nice to me. My mom, Little Mother, made the dress for Little Nell."

Then Mr Loeser’s sister wrote: "I'm (Lynn) Marrilyn Loeser Connell, the granddaughter of 'Little Nell'. My brother was very kind to write to you about our grandmother. I am writing a book for our three grandchildren. It will include as much history of our families and memories that I could squeeze into 1 small book for each. They are all grown now.(over 20). While looking though all of the articles and photos, I found a little note with some photos and an article about Little Nell from years ago. etc. I had heard that my grandmother had stood for a sculptor, but that was hear-say. It was wonderful to find the little note stating that she indeed had stood for Elwell. After that I went on to the web and found the rest of the information. That's how I knew how to get in touch with the Dickens Fellowship."

Florence Lucia Pomero

"P.S. Our grandmother grew up to be a most beautiful woman with much grace and charm."

Another View

Overland Monthly and the Out West magazine - 1898, Volume 32, Issue 89, p.204:

When 'Little Nell' was in preparation, there came a period when it seemed almost impossible for the artist to continue his work. He had been unable to find a face from which to draw his inspiration, one that should convey the tenderness, patience, and love, of the one he had in mind. Some time went by before finally the difficulty was solved. Mr. Elwell was invited to attend a concert, where the music was delightful. As the second part of the programme was beginning, he saw before him the Little Nell of his dreams, in the face of a lovely little girl. Gazing long and intently at the child, he explained to her father, as his reason for so doing, that he was making a statue of Little Nell, and that his daughter was the ideal of the subject. Very shortly after, the sculptor was in his studio, and worked far into the night, until he had reproduced the spirit of the child's face he had seen at the concert.

A pathetic incident occurred about the time the statue was finished. The father of the child expressed a desire to see the work. Accordingly he was invited to the studio on a certain Monday morning: but he died the preceding Saturday night. Mr. Elwell often refers to Little Nell as his only daughter. Many times has her dear little figure and loving face come to him; she has never forsaken him, and has always been to him a real being.

Frank Edwin Elwell passed away on January 23, 1922, in Darien, Connecticut at the age of 63.

Some connections between

Charles Dickens, Kate Douglas Wiggin and Frank Elwell

by Herb Moskovitz

Most Dickensians know that Kate Douglas Wiggin, author of such books as Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, met Charles Dickens on a train going from Portland, Maine to Boston when she was a young girl of twelve. She wrote of her experience in a small book called A Child's Journey with Dickens. I have just learned of other connections between Dickens, Kate Wiggin and Frank Elwell, sculptor of the beloved Dickens statue in Clark Park.

Susan Wickham from Dorset England wrote to Jane King of the Philadelphia branch with two questions she hoped a Philadelphian could answer. One was a question about Kate Douglas Wiggin, who was born in Philadelphia, and the other question was if we could identify the young girl who posed for Little Nell in the Dickens Statue in Clark Park. Jane passed the questions to me but I didn't know the answer to either question. However, I recently learned of a woman in West Chester, New York who is an expert on Kate Wiggin.

Her name is Glenys Tarlow and hoping she could answer the Wiggin question, I called her. She told me that she has never visited the Dickens statue in Clark Park and asked if I knew anything about it. I told her a bit of the history of the statue and the sculptor, Frank Elwell. She then told me that Kate Douglas Wiggin had rented Frank Elwell's house at 131 West 11th Street in NYC for two years starting in 1895 to 1897. She said she had wondered how they had met and when I told her that Elwell exhibited the statue at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893, it occurred to her that they probably met there because Wiggin was in charge of a Literary Exhibit in the Women's Building at the Exhibition. Kate Douglas Wiggin describes the house in chapter 28 of her autobiography:

(The house) was comfortable and homelike, but the real magnet that drew us to the house was the sculptor's studio, reached by a broad passage from the street door. It was an enormous room, two stories high, built out over the land in the rear, for the sculptor modeled large figures and groups. The walls were of mellowed brick; and being a studio it was lighted from the top. There was also a magnificent fireplace into which one could fling logs a yard long. Near by was a curious erection of bricks about five feet square, with accompaniments that made it a sculptor's forge. This seemed a difficult object to combine with other furnishings for a room destined to be devoted to wonderful parties; however George (Riggs...her husband) solved the difficulty by inventing a sizable wrought-iron brazier with a gridiron at the top and coals underneath, and lo! we had a place to broil English chops, lobsters, oysters, and other goodies, so that in time we no longer called the place a studio, but the Michelangelo Grill Room. (The choice of this title was a conscientious effort to placate the sculptor, although he was abroad and had given us carte blanche to do anything we liked.)

...The Grill Room was a very expensive but a very precious toy. For our first dinner I bought many plants, and the new butler arranged flowers in all the cut-glass bowls and vases that had been among our wedding gifts. When the feast was over, the last guest gone, and the lights and the fires extinguished, a whirling snowstorm descended, and next morning plants were frozen and all the cut-glass broken. The party was worth it, we declared, for it was a dinner for Sir Henry Irving and Ellen Terry; the other guests being Mark Twain....(and she goes on to list other notables of the period.)

There was a quaint little balcony (see photo above) or gallery across the entrance end of the room, wide enough for an upright piano and high enough for music or theatricals. This was lighted with two tall rose-colored lamps, and there from time to time "The Singing Girls" a quartette of which I was the godmother, gave us old English songs. Ms. Tarlow has visited the house and although Elwell lived alone there, it is now divided into many apartments. Two young men are living in what was once Elwell's studio. It is no doubt the one where he created the Dickens Statue. She said they have decorated it very nicely.

The David Copperfield Library

Kate Douglas Wiggin was also involved in a library project in the house on Johnson Street where young Dickens lived when he was about thirteen. Ms. Tarlow sent me photocopies of pages from The Dickensian from January 1921 through autumn of 1932 and from a book called New Roads to Childhood that tell the story of the attempt to establish the library.

Anne Carroll Moore, First Superintendent of Children's Work at the New York Public Library, and a friend of Kate Douglas Wiggin wrote of the David Copperfield Library in New Roads to Childhood in 1939.

"The story of David Copperfield's Library begins with the eleventh chapter of David Copperfield, with its intimate record of what we now know to have been Charles Dickens' daily life with the Micawbers. 'My address,' said Mr. Micawber, 'is Windsor Terrace, City Road. I - in short, 'said Mr. Micawber, with the same genteel air, and in another burst of confidence, 'I live there.'"

The small house in Windsor Terrace was shabby in Mr. Micawber's day. It may be remembered that he often went to bed "making a calculation of the expense of putting bow windows to the house 'in case anything turned up.'"

Nearly a century went by before anything did turn up, and then one day in 1911 the London County Council appeared in Johnson Street, Somers Town, bringing a small tablet with this inscription:

Charles Dickens

1812 - 1870

Novelist

Lived Here

in Boyhood

In the spring of 1920, the Reverend J. Brett Langstaff discovered the house, which was sometimes called a "Tiny Tim of a house." The house was three stories high and unchanged from the time that Dickens lived there. He wrote, "It seems to me that if one could make in this David Copperfield house a happy book world for the boys and girls it would in some way make up for the miserable times Dickens had when as a lad of thirteen he lodged there with Mrs. Pipchin, because his father (Mr. Micawber) was most of the time in a debtor's prison."

His plan was published in a circular that appeared throughout England with endorsements of the idea from Henry Fielding Dickens, James Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, H. G. Wells and other notables.

From The Dickensian

January 1921:

The movement for establishing the first Children's library for England in the home of Charles Dickens's boyhood at 13 Johnson Street, Somers Town, has taken definite form. The house, in the course of events, would be torn down within the next few months to make way for a large building scheme. Rather that this should be done it is intended to retain it and convert it into a library for youngsters between the ages of eight and fourteen, furnish it in an appropriate and bright manner, and endow it. An influential committee has been got together, and many authors and public men have expressed their approval and sympathy and promised help in other ways.

On November 1, 1923 the deed to the house and the two houses on either side of it were given to the Lord Mayor of St. Pancras on behalf of the Children's Library Movement. The library was called The David Copperfield Library for Children.

The library is described in great detail by Ms. Moore. It sounds absolutely charming with low bookshelves filled with about five hundred books donated by American and British authors, illustrators and publishers. The French government donated books, too. The Dickens lovers of the staff of the New York Public Library had L. Leslie Brooke create large crayon panels of Dick Whittington, the Babes in the Woods and the children of China, Canada, Russia and India.

Raven Hill, Frank Reynolds, H. M. Bateman and other illustrators also created artwork for the library. A letter from Kate Douglas Wiggin was also on display.

On page 122 of New Roads to Childhood, the handwritten letter from Kate Douglas Wiggin was published.

To the dear readers of the David Copperfield Library

I began to love Charles Dickens and to read him when I was a little country mouse eight years old; and where I was eleven, (Oh! wonderful good fortune!) I travelled with him on a certain railway journey between Maine and Massachusetts. It was a magical, a miraculous trip of two hours, during which my child's hand was in his, and his arm around my waist so that in that long talk we became real friends. I have told the tale in my "Child's Journey with Dickens." Some of you may have read it -- and it will explain my interest - in the David Copperfield Library.

There are many other Americans who love and read Dickens, and want to share in making this library in the house where he lived as a boy. One of them, Annie Carroll Moore, who chooses the children's books for the New York Public Library has made this representative selection which I am asked to send as a gift from the generous American publishers, whose names appear in each of their presentation volumes.

New York November 1921 Kate Douglas Wiggin

But the St. Pancras Borough Council abandoned support for the library and although a group of enthusiasts helped the library continue for a short time, The Dickensian of autumn 1932 reported:

It is sad to record that the David Copperfield Library in the house of Dickens's boyhood in Johnson Street is no more. It was an oasis in the desert of Camden Town and much appreciated by the youngsters of the neighbourhood. When the Fellowship heard that the trustees were giving up the place, they tried hard to save it, but without success. The house is in a condemned area and will shortly be demolished. It is to be hoped that the tablet recording Dickens's association with the house will be preserved and incorporated in any new building to be erected on the site.

A sad end to a worthwhile project.