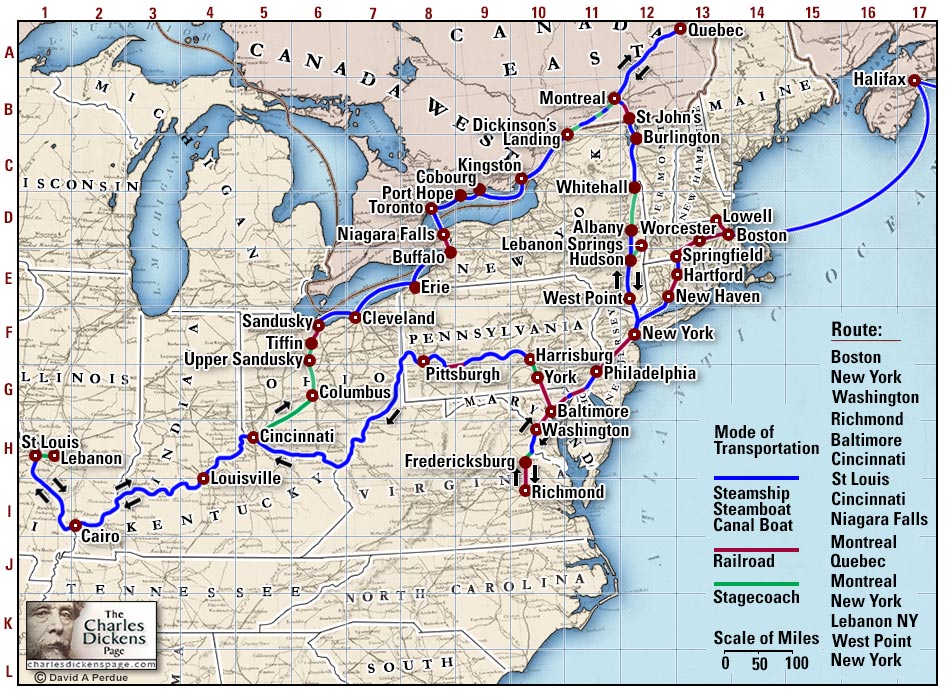

Dickens in America > Map of Dickens' 1842 Travels

The Charles Dickens Page

Charles Dickens - Travels in America and Canada 1842

More information on the places Dickens visited:

Sources

American Notes - Taken from the published account.

Letters - The Letters of Charles Dickens - Pilgrim Edition

Halifax, Nova Scotia

(map B-17) January 20, 1842

American Notes - The town is built on the side of a hill, the highest point being commanded by a strong fortress, not yet quite finished. Several streets of good breadth and appearance extend from its summit to the water-side, and are intersected by cross streets running parallel with the river. The houses are chiefly of wood. The market is abundantly supplied; and provisions are exceedingly cheap. The weather being unusually mild at that time for the season of the year, there was no sleighing; but there were plenty of those vehicles in yards and bye-places, and some of them, from the gorgeous quality of their decorations, might have ‘gone on’ without alteration as triumphal cars in a melo-drama at Astley's. The day was uncommonly fine; the air bracing and healthful; the whole aspect of the town cheerful, thriving, and industrious.

We lay there seven hours, to deliver and exchange the mails. At length, having collected all our bags and all our passengers (including two or three choice spirits, who, having indulged too freely in oysters and champagne, were found lying insensible on their backs in unfrequented streets), the engines were again put in motion, and we stood off for Boston (American Notes, p. 22).

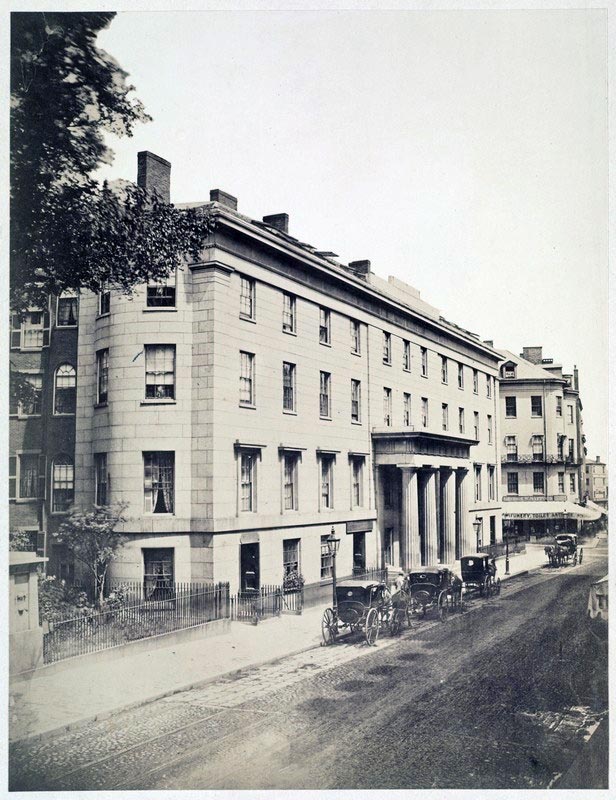

Boston, Massachusetts

(map D-13) January 22 - February 5, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Tremont House

American Notes - The city is a beautiful one, and cannot fail, I should imagine, to impress all strangers very favourably. The private dwelling-houses are, for the most part, large and elegant; the shops extremely good; and the public buildings handsome. The State House is built upon the summit of a hill, which rises gradually at first, and afterwards by a steep ascent, almost from the water’s edge. In front is a green enclosure, called the Common. The site is beautiful: and from the top there is a charming panoramic view of the whole town and neighbourhood (American Notes, p. 26-27).

Above all, I sincerely believe that the public institutions and charities of this capital of Massachusetts are as nearly perfect, as the most considerate wisdom, benevolence, and humanity, can make them. I never in my life was more affected by the contemplation of happiness, under circumstances of privation and bereavement, than in my visits to these establishments (American Notes, p. 28).

Letters - To Thomas Mitton (Dickens' solicitor) 31 Jan 1842 from Tremont House, Boston - I can give you no conception of my welcome here. There never was a King or Emperor upon the Earth, so cheered, and followed by crowds, and entertained in Public at splendid balls and dinners, and waited on by public bodies and deputations of all kinds...If I go out in a carriage, the crowd surround it and escort me home. If I go to the Theatre, the whole house (crowded to the roof) rises as one man, and the timbers ring again. You cannot imagine what it is (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 43).

Lowell, Massachusetts

(map D-13) February 3, 1842

The female mill workers in Lowell called themselves the Lowell Girls

American Notes - I was met at the station [Dickens' first trip on an American railroad] at Lowell by a gentleman intimately connected with the management of the factories there; and gladly putting myself under his guidance, drove off at once to that quarter of the town in which the works, the object of my visit, were situated. Although only just of age - for if my recollection serve me, it has been a manufacturing town barely one-and-twenty years - Lowell is a large, populous, thriving place... (American Notes, p. 65)

I happened to arrive at the first factory just as the dinner hour was over, and the girls [mill girls] were returning to their work; indeed the stairs of the mill were thronged with them as I ascended. They were all well dressed, but not to my thinking above their condition; for I like to see the humbler classes of society careful of their dress and appearance, and even, if they please, decorated with such little trinkets as come within the compass of their means... (American Notes, p. 66)

These girls, as I have said, were all well dressed: and that phrase necessarily includes extreme cleanliness. They had serviceable bonnets, good warm cloaks, and shawls; and were not above clogs and pattens. Moreover, there were places in the mill in which they could deposit these things without injury; and there were conveniences for washing. They were healthy in appearance, many of them remarkably so, and had the manners and deportment of young women: not of degraded brutes of burden... (American Notes, p. 66)

In this brief account of Lowell, and inadequate expression of the gratification it yielded me, and cannot fail to afford to any foreigner to whom the condition of such people at home is a subject of interest and anxious speculation, I have carefully abstained from drawing a comparison between these factories and those of our own land. Many of the circumstances whose strong influence has been at work for years in our manufacturing towns have not arisen here; and there is no manufacturing population in Lowell, so to speak: for these girls (often the daughters of small farmers) come from other States, remain a few years in the mills, and then go home for good (American Notes, p. 69-70).

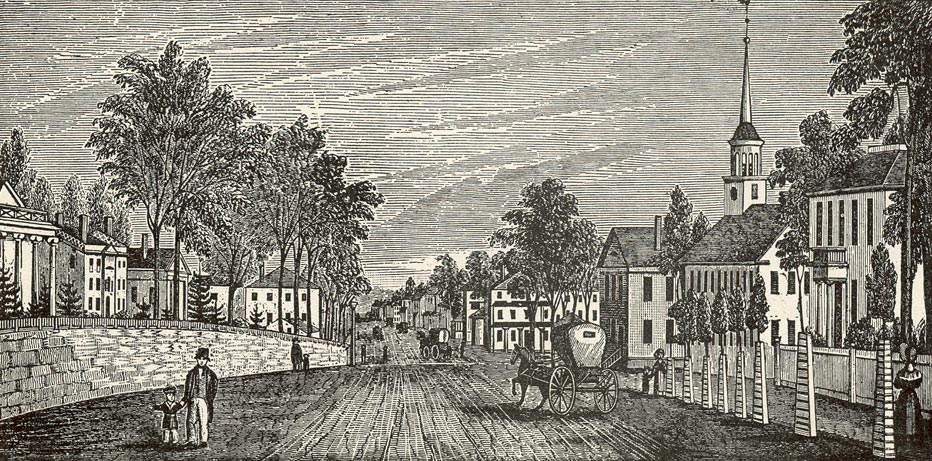

Worcester, Massachusetts

(map D-13) February 5-7, 1842

Main Street Worcester, MA 1839

American Notes - Leaving Boston on the afternoon of Saturday the fifth of February, we proceeded by another railroad to Worcester: a pretty New England town, where we had arranged to remain under the hospitable roof of the Governor of the State [John Davis 1787-1854], until Monday morning.

These towns and cities of New England (many of which would be villages in Old England), are as favourable specimens of rural America, as their people are of rural Americans. The well-trimmed lawns and green meadows of home are not there; and the grass, compared with our ornamental plots and pastures, is rank, and rough, and wild: but delicate slopes of land, gently-swelling hills, wooded valleys, and slender streams, abound. Every little colony of houses has its church and school-house peeping from among the white roofs and shady trees; every house is the whitest of the white; every Venetian blind the greenest of the green; every fine day's sky the bluest of the blue. A sharp dry wind and a slight frost had so hardened the roads when we alighted at Worcester, that their furrowed tracks were like ridges of granite. There was the usual aspect of newness on every object, of course. All the buildings looked as if they had been built and painted that morning, and could be taken down on Monday with very little trouble. In the keen evening air, every sharp outline looked a hundred times sharper than ever. The clean cardboard colonnades had no more perspective than a Chinese bridge on a tea-cup, and appeared equally well calculated for use. The razor-like edges of the detached cottages seemed to cut the very wind as it whistled against them, and to send it smarting on its way with a shriller cry than before. Those slightly-built wooden dwellings behind which the sun was setting with a brilliant lustre, could be so looked through and through, that the idea of any inhabitant being able to hide himself from the public gaze, or to have any secrets from the public eye, was not entertainable for a moment. Even where a blazing fire shone through the uncurtained windows of some distant house, it had the air of being newly lighted, and of lacking warmth; and instead of awakening thoughts of a snug chamber, bright with faces that first saw the light round that same hearth, and ruddy with warm hangings, it came upon one suggestive of the smell of new mortar and damp walls (American Notes, p. 71-72).

Springfield, Massachusetts

(map E-13) February 7, 1842

American Notes - We went on next morning, still by railroad, to Springfield. From that place to Hartford, whither we were bound, is a distance of only five-and-twenty miles, but at that time of the year the roads were so bad that the journey would probably have occupied ten or twelve hours. Fortunately, however, the winter having been unusually mild, the Connecticut River was 'open,' or, in other words, not frozen. The captain of a small steamboat was going to make his first trip for the season that day (the second February trip, I believe, within the memory of man), and only waited for us to go on board. Accordingly, we went on board, with as little delay as might be. He was as good as his word, and started directly (American Notes, p. 72).

Hartford, Connecticut

(map E-13) February 7-11, 1842

Hartford Connecticut in the 1840s

American Notes - After two hours and a half of this odd travelling (including a stoppage at a small town, where we were saluted by a gun considerably bigger than our own chimney), we reached Hartford, and straightway repaired to an extremely comfortable hotel [City Hotel]: except, as usual, in the article of bedrooms, which, in almost every place we visited, were very conducive to early rising. We tarried here, four days. The town is beautifully situated in a basin of green hills; the soil is rich, well-wooded, and carefully improved. It is the seat of the local legislature of Connecticut, which sage body enacted, in bygone times, the renowned code of 'Blue Laws,' in virtue whereof, among other enlightened provisions, any citizen who could be proved to have kissed his wife on Sunday, was punishable, I believe, with the stocks. Too much of the old Puritan spirit exists in these parts to the present hour; but its influence has not tended, that I know, to make the people less hard in their bargains, or more equal in their dealings... (American Notes, p. 73)

In Hartford stands the famous oak in which the charter of King Charles was hidden. It is now inclosed in a gentleman's garden. In the State House is the charter itself. I found the courts of law here, just the same as at Boston; the public institutions almost as good. The Insane Asylum is admirably conducted, and so is the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb (American Notes, p. 74).

I shall always entertain a very pleasant and grateful recollection of Hartford. It is a lovely place, and I had many friends there, whom I can never remember with indifference. We left it with no little regret on the evening of Friday the 11th, and travelled that night by railroad to New Haven (American Notes, p. 76-77).

New Haven, Connecticut

(map E-12) February 11-12, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Tontine Hotel, shown here in the early 1900s

American Notes - New Haven, known also as the City of Elms, is a fine town. Many of its streets (as its alias sufficiently imports) are planted with rows of grand old elm-trees; and the same natural ornaments surround Yale College [Yale University, founded 1701], an establishment of considerable eminence and reputation. The various departments of this Institution are erected in a kind of park or common in the middle of the town, where they are dimly visible among the shadowing trees. The effect is very like that of an old cathedral yard in England; and when their branches are in full leaf, must be extremely picturesque. Even in the winter time, these groups of well-grown trees, clustering among the busy streets and houses of a thriving city, have a very quaint appearance: seeming to bring about a kind of compromise between town and country; as if each had met the other half-way, and shaken hands upon it; which is at once novel and pleasant.

After a night’s rest, we rose early, and in good time went down to the wharf, and on board the packet New York, for New York. This was the first American steamboat of any size that I had seen (American Notes, p. 77).

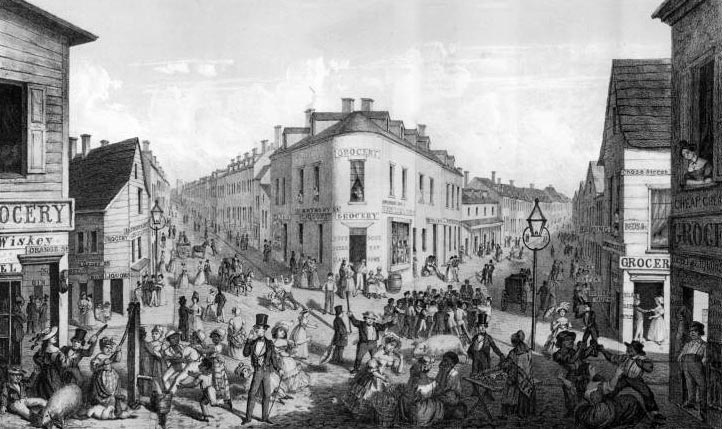

New York, New York

(map F-12) February 12-March 5, June 2-3, June 6-7, 1842

Dickens visited the notorious Tombs Prison in New York

American Notes - The beautiful metropolis of America is by no means so clean a city as Boston, but many of its streets have the same characteristics; except that the houses are not quite so fresh-coloured, the sign-boards are not quite so gaudy, the gilded letters not quite so golden, the bricks not quite so red, the stone not quite so white, the blinds and area railings not quite so green, the knobs and plates upon the street doors, not quite so bright and twinkling. There are many bye-streets, almost as neutral in clean colours, and positive in dirty ones, as bye-streets in London; and there is one quarter, commonly called the Five Points,1 which, in respect of filth and wretchedness, may be safely backed against Seven Dials, or any other part of famed St Giles’s.

The great promenade and thoroughfare, as most people know, is Broadway; a wide and bustling street, which, from the Battery Gardens to its opposite termination in a country road, may be four miles long. Shall we sit down in an upper floor of the Carlton House Hotel (situated in the best part of this main artery of New York), and when we are tired of looking down upon the life below, sally forth arm-in-arm, and mingle with the stream?

The Streets of New York (Five Points) 1827

Warm weather! The sun strikes upon our heads at this open window, as though its rays were concentrated through a burning-glass; but the day is in its zenith, and the season an unusual one. Was there ever such a sunny street as this Broadway! The pavement stones are polished with the tread of feet until they shine again; the red bricks of the houses might be yet in the dry, hot kilns; and the roofs of those omnibuses look as though, if water were poured on them, they would hiss and smoke, and smell like half-quenched fires. No stint of omnibuses here! Half-a-dozen have gone by within as many minutes. Plenty of hackney cabs and coaches too; gigs, phaetons, large-wheeled tilburies, and private carriages - rather of a clumsy make, and not very different from the public vehicles, but built for the heavy roads beyond the city pavement. Negro coachmen and white; in straw hats, black hats, white hats, glazed caps, fur caps; in coats of drab, black, brown, green, blue, nankeen, striped jean and linen; and there, in that one instance (look while it passes, or it will be too late), in suits of livery. Some southern republican that, who puts his blacks in uniform, and swells with Sultan pomp and power. Yonder, where that phaeton with the well-clipped pair of grays has stopped - standing at their heads now - is a Yorkshire groom, who has not been very long in these parts, and looks sorrowfully round for a companion pair of top-boots, which he may traverse the city half a year without meeting. Heaven save the ladies, how they dress! We have seen more colours in these ten minutes, than we should have seen elsewhere, in as many days. What various parasols! what rainbow silks and satins! what pinking of thin stockings, and pinching of thin shoes, and fluttering of ribbons and silk tassels, and display of rich cloaks with gaudy hoods and linings! The young gentlemen are fond, you see, of turning down their shirt-collars and cultivating their whiskers, especially under the chin; but they cannot approach the ladies in their dress or bearing, being, to say the truth, humanity of quite another sort (American Notes, p. 80-81).

Letters Vol 3 Pg 70: To John Forster 17 Feb 1842 from Carlton House, New York - About half past 2 [pm February 12], we arrived here. In half an hour more, we reached this hotel (Carlton House on Broadway], where a very splendid suite of rooms was prepared for us; and where everything is very comfortable, and no doubt (as at Boston) enormously dear [$2.00 a day] (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 70).

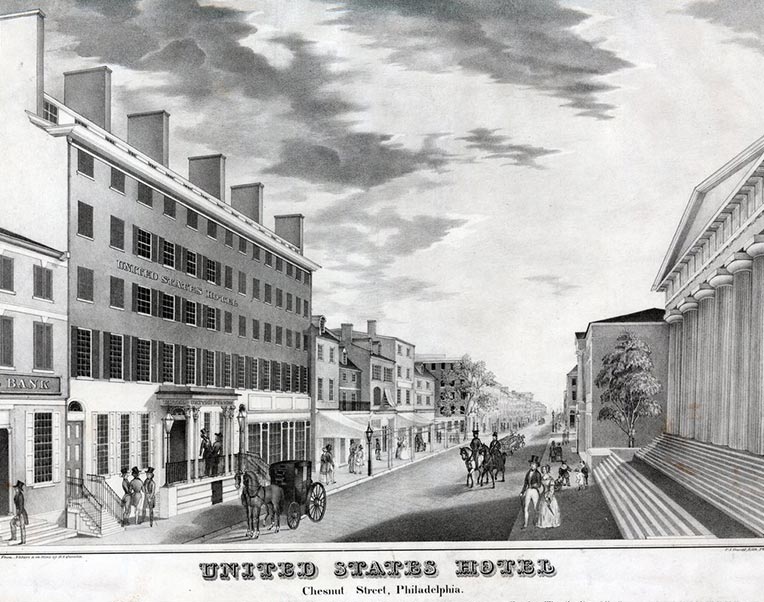

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

(map G-11) March 5-9, 1842

Dickens stayed at the United States Hotel on Chestnut Street

American Notes - The journey from New York to Philadelphia, is made by railroad, and two ferries; and usually occupies between five and six hours (American Notes, p. 97).

It is a handsome city, but distractingly regular. After walking about it for an hour or two, I felt that I would have given the world for a crooked street. The collar of my coat appeared to stiffen, and the brim of my hat to expand, beneath its quakerly influence (American Notes, p. 98).

There are various public institutions. Among them a most excellent Hospital - a quaker establishment, but not sectarian in the great benefits it confers; a quiet, quaint old Library, named after Franklin; a handsome Exchange and Post Office; and so forth. In connection with the quaker Hospital, there is a picture by West [Benjamin West], which is exhibited for the benefit of the funds of the institution. The subject is, our Saviour healing the sick, and it is, perhaps, as favourable a specimen of the master as can be seen anywhere. Whether this be high or low praise, depends upon the reader's taste (American Notes, p. 98).

In the outskirts, stands a great prison, called the Eastern Penitentiary: conducted on a plan peculiar to the state of Pennsylvania. The system here, is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong (American Notes, p. 99).

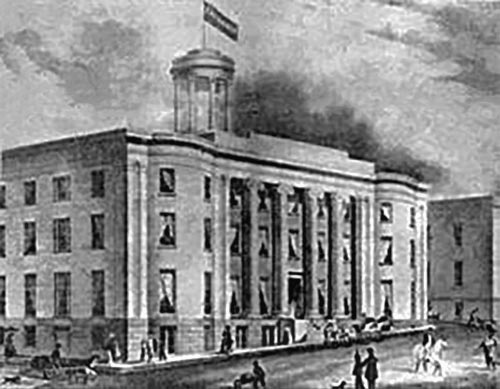

Washington D.C.

(map H-10) March 9-16, March 20, 1842

When Dickens visited the US Capitol still had the old copper dome

American Notes - We reached Washington at about half-past six that evening, and had upon the way a beautiful view of the Capitol, which is a fine building of the Corinthian order, placed upon a noble and commanding eminence. Arrived at the hotel, I saw no more of the place that night; being very tired, and glad to get to bed (American Notes, p. 115).

Take the worst parts of the City Road and Pentonville, preserving all their oddities, but especially the small shops and dwellings, occupied there (but not in Washington) by furniture-brokers, keepers of poor eating-houses, and fanciers of birds. Burn the whole down; build it up again in wood and plaster; widen it a little; throw in part of St John’s Wood; put green blinds outside all the private houses, with a red curtain and a white one in every window; plough up all the roads; plant a great deal of coarse turf in every place where it ought not to be; erect three handsome buildings in stone and marble, anywhere, but the more entirely out of everybody’s way the better; call one the Post Office, one the Patent Office, and one the Treasury; make it scorching hot in the morning, and freezing cold in the afternoon, with an occasional tornado of wind and dust; leave a brick-field without the bricks, in all central places where a street may naturally be expected: and that’s Washington.

The hotel in which we live [Fuller's Hotel (became the Willard Hotel in 1847) at 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue], is a long row of small houses fronting on the street, and opening at the back upon a common yard, in which hangs a great triangle. Whenever a servant is wanted, somebody beats on this triangle from one stroke up to seven, according to the number of the house in which his presence is required; and as all the servants are always being wanted, and none of them ever come, this enlivening engine is in full performance the whole day through. Clothes are drying in the same yard; female slaves, with cotton handkerchiefs twisted round their heads are running to and fro on the hotel business; black waiters cross and recross with dishes in their hands; two great dogs are playing upon a mound of loose bricks in the centre of the little square; a pig is turning up his stomach to the sun, and grunting 'that's comfortable!'; and neither the men, nor the women, nor the dogs, nor the pig, nor any created creature, takes the smallest notice of the triangle, which is tingling madly all the time (American Notes, p. 115-116).

It is sometimes called the City of Magnificent Distances, but it might with greater propriety be termed the City of Magnificent Intentions; for it is only on taking a bird's-eye view of it from the top of the Capitol that one can at all comprehend the vast designs of its projector, an aspiring Frenchman. Spacious avenues that begin in nothing, and lead nowhere; streets, mile long, that only want houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament -- are its leading features (American Notes, p. 116).

Richmond, Virginia

(map I-10) March 17-20, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond

American Notes - It was between six and seven o'clock in the evening, when we drove to the hotel: in front of which, and on the top of the broad flight of steps leading to the door, two or three citizens were balancing themselves on rocking-chairs, and smoking cigars. We found it a very large and elegant establishment, and were as well entertained as travellers need desire to be (American Notes, p. 134).

The same decay and gloom that overhang the way by which it is approached, hover above the town of Richmond. There are pretty villas and cheerful houses in its streets, and Nature smiles upon the country round; but jostling its handsome residences, like slavery itself going hand in hand with many lofty virtues, are deplorable tenements, fences unrepaired, walls crumbling into ruinous heaps. Hinting gloomily at things below the surface, these, and many other tokens of the same description, force themselves upon the notice, and are remembered with depressing influence, when livelier features are forgotten (American Notes, p. 136).

Letters - To John Forster 21 Mar 1842 from Fuller's Hotel, Washington - [On leaving Richmond] My heart is lightened as if a great load had been taken from it, when I think that we are turning our backs on this accursed and detested system. I really don't think I could have borne it any longer. It is all very well to say "be silent on the subject." They won't let you be silent. They will ask you what you think of it; and will expatiate on slavery as if it were on of the greatest blessings of mankind (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 140-141).

Baltimore, Maryland

(map G-10) March 21-24, 1842

Dickens stayed at Barnum's Hotel in Baltimore

American Notes - ...we returned to Washington by the way we had come (there were two constables on board the steam-boat, in pursuit of runaway slaves), and halting there again for one night, went on to Baltimore next afternoon. The most comfortable of all the hotels of which I had any experience in the United States, and they were not a few, is Barnum’s in that city: where the English traveller will find curtains to his bed, for the first and probably the last time, in America; and where he will be likely to have enough water for washing himself, which is not at all a common case.

This capital of the state of Maryland is a bustling, busy town, with a great deal of traffic of various kinds, and in particular of water commerce. That portion of the town which it most favours is none of the cleanest, it is true; but the upper part is of a very different character, and has many agreeable streets and public buildings. The Washington Monument, which is a handsome pillar with a statue on its summit; the Medical College; and the Battle Monument in memory of an engagement with the British at North Point; are the most conspicuous among them (American Notes, p. 137).

York, Pennsylvania

(map G-10) March 24, 1842

Letters - To John Forster 28 Mar 1842 on board a canal boat headed for Pittsburgh - We left Baltimore last Thursday the twenty-fourth at half-past eight in the morning, by railroad; and got to a place called York about twelve. There we dined, and took a stage-coach for Harrisburgh; twenty-five miles further. This stage-coach was like nothing so much as the body of one of the swings you see at a fair set upon four wheels and roofed and covered at the sides with painted canvas. There were twelve inside! I, thank my stars, was on the box. The luggage was on the roof; among it, a good-sized dining table, and a big rocking-chair. We also took up an intoxicated gentleman, who sat for ten miles between me and the coachman; and another intoxicated gentleman who got up behind, but in the course of a mile or two fell off without hurting himself, and was seen in the distant perspective reeling back to the grog-shop where we had found him (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 167).

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

(map F-10) March 24-25, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Eagle Hotel in Harrisburg. It became the Bolton Hotel in the 1860s

American Notes - ...we emerged upon the streets of Harrisburg, whose feeble lights, reflected dismally from the wet ground, did not shine out upon a very cheerful city. We were soon established in a snug hotel, which though smaller and far less splendid than many we put up at, it raised above them all in my remembrance, by having for its landlord [Henry Buehler] the most obliging, considerate, and gentlemanly person I ever had to deal with.

As we were not to proceed upon our journey until the afternoon, I walked out, after breakfast the next morning, to look about me; and was duly shown a model prison on the solitary system, just erected, and as yet without an inmate; the trunk of an old tree to which Harris, the first settler here (afterwards buried under it), was tied by hostile Indians, with his funeral pile about him, when he was saved by the timely appearance of a friendly party on the opposite shore of the river; the local legislature (for there was another of those bodies here again, in full debate); and the other curiosities of the town (American Notes, p. 142).

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

(map G-8) March 28 - April 1, 1842

Dickens traveled from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh aboard a canal boat on the Pennsylvania Canal

American Notes - We had left Harrisburgh on Friday [Aboard a canal boat on the Pennsylvania Canal]. On Sunday morning we arrived at the foot of the mountain, which is crossed by railroad. There are ten inclined planes; five ascending, and five descending; the carriages are dragged up the former, and let slowly down the latter, by means of stationary engines; the comparatively level spaces between, being traversed, sometimes by horse, and sometimes by engine power, as the case demands. Occasionally the rails are laid upon the extreme verge of a giddy precipice; and looking from the carriage window, the traveller gazes sheer down, without a stone or scrap of fence between into the mountain depths below. The journey is very carefully made, however; only two carriages travelling together; and while proper precautions are taken, is not to be dreaded for its dangers (American Notes, p. 153).

On the Monday evening, furnace fires and clanking hammers on the banks of the canal, warned us that we approached the termination of this part of our journey. After going through another dreamy place – a long aqueduct across the Alleghany River, which was stranger than the bridge at Harrisburgh, being a vast low wooden chamber full of water – we emerged upon that ugly confusion of backs of buildings and crazy galleries and stairs, which always abuts on water, whether it be river, sea, canal, or ditch: and were at Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh is like Birmingham in England; at least its townspeople say so. Setting aside the streets, the shops, the houses, waggons, factories, public buildings, and population, perhaps it may be. It certainly has a great quantity of smoke hanging about it, and is famous for its iron-works. Besides the prison to which I have already referred, this town contains a pretty arsenal and other institutions. It is very beautifully situated on the Alleghany River, over which there are two bridges; and the villas of the wealthier citizens sprinkled about the high grounds in the neighbourhood, are pretty enough. We lodged at a most excellent hotel, and were admirably served. As usual it was full of boarders, was very large, and had a broad colonnade to every story of the house. We tarried here, three days (American Notes, p. 154).

Learn more about the journey

From Pittsburgh to Cincinnati in a Western Steamboat

From Pittsburgh to Cincinnati in a Western Steamboat

American Notes - Chapter XI

This chapter describes the fascinating trip aboard the steamboat Messenger down the Ohio river during the heyday of the American steamboat (American Notes, p. 156-164).

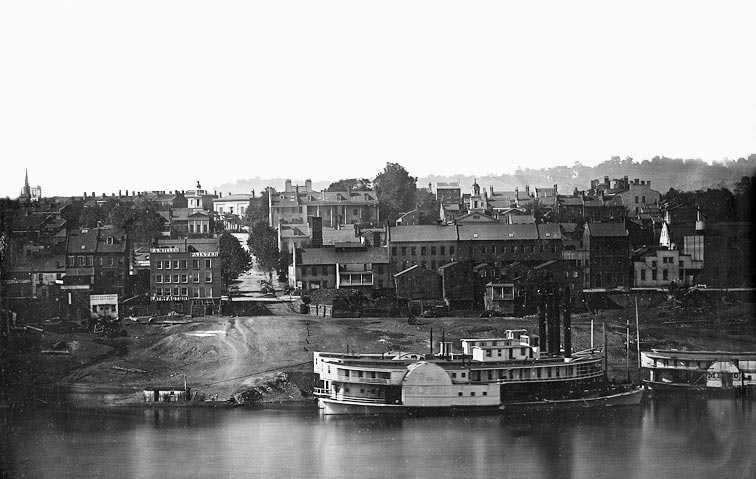

Cincinnati, Ohio

(map H-5) April 4-6, 19-20, 1842

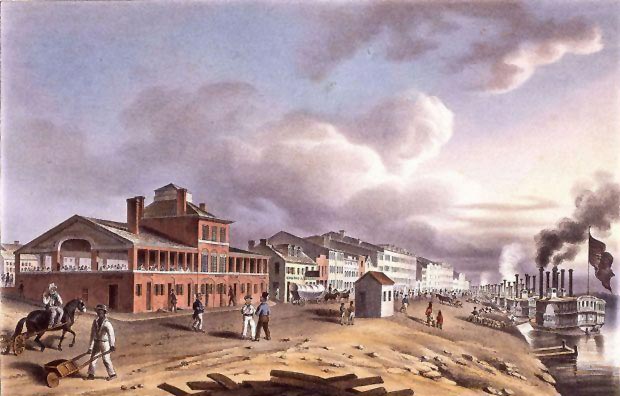

The Cincinnati riverfront in the 1840s

American Notes - Cincinnati is a beautiful city; cheerful, thriving, and animated. I have not often seen a place that commends itself so favourably and pleasantly to a stranger at the first glance as this does: with its clean houses of red and white, its well-paved roads, and footways of bright tile. Nor does it become less prepossessing on a closer acquaintance. The streets are broad and airy, the shops extremely good, the private residences remarkable for their elegance and neatness. There is something of invention and fancy in the varying styles of these latter erections, which, after the dull company of the steamboat, is perfectly delightful, as conveying an assurance that there are such qualities still in existence. The disposition to ornament these pretty villas and render them attractive, leads to the culture of trees and flowers, and the laying out of well-kept gardens, the sight of which, to those who walk along the streets, is inexpressibly refreshing and agreeable. I was quite charmed with the appearance of the town, and its adjoining suburb of Mount Auburn; from which the city, lying in an amphitheatre of hills, forms a picture of remarkable beauty, and is seen to great advantage (American Notes, p. 162).

Cincinnati is honourably famous for its free schools, of which it has so many that no person's child among its population can, by possibility, want the means of education, which are extended, upon an average, to four thousand pupils, annually. I was only present in one of these establishments during the hours of instruction. In the boys' department, which was full of little urchins (varying in their ages, I should say, from six years old to ten or twelve), the master offered to institute an extemporary examination of the pupils in algebra; a proposal, which, as I was by no means confident of my ability to detect mistakes in that science, I declined with some alarm. In the girls' school, reading was proposed; and as I felt tolerably equal to that art, I expressed my willingness to hear a class. Books were distributed accordingly, and some half-dozen girls relieved each other in reading paragraphs from English History. But it seemed to be a dry compilation, infinitely above their powers; and when they had blundered through three or four dreary passages concerning the Treaty of Amiens, and other thrilling topics of the same nature (obviously without comprehending ten words), I expressed myself quite satisfied. It is very possible that they only mounted to this exalted stave in the Ladder of Learning for the astonishment of a visitor; and that at other times they keep upon its lower rounds; but I should have been much better pleased and satisfied if I had heard them exercised in simpler lessons, which they understood (American Notes, p. 163-164).

The society with which I mingled, was intelligent, courteous, and agreeable. The inhabitants of Cincinnati are proud of their city as one of the most interesting in America: and with good reason: for beautiful and thriving as it is now, and containing, as it does, a population of fifty thousand souls, but two-and-fifty years have passed away since the ground on which it stands (bought at that time for a few dollars) was a wild wood, and its citizens were but a handful of dwellers in scattered log huts upon the river's shore (American Notes, p. 164).

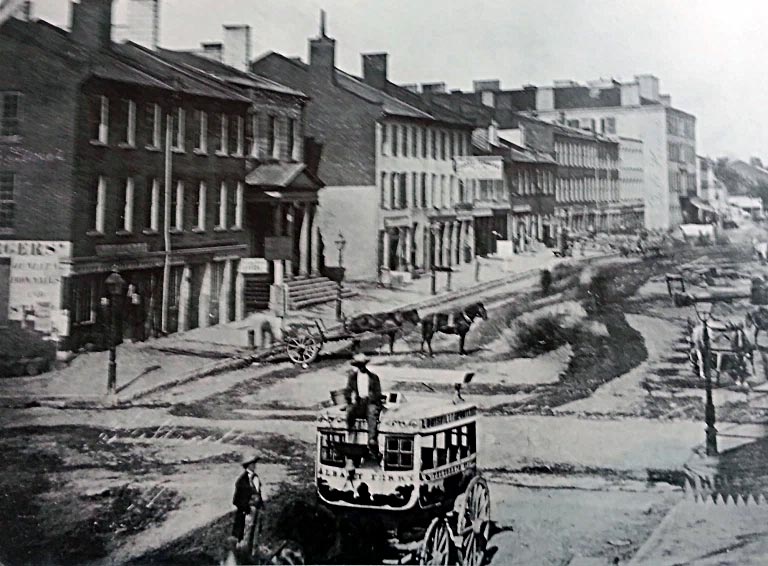

Louisville, Kentucky

(map I-4) April 6-7, 17-18, 1842

The original Galt House, where Dickens stayed, is on the right in this 1850 photo

American Notes - Leaving Cincinnati at eleven o’clock in the forenoon, we embarked for Louisville in the Pike steam-boat, which, carrying the mails, was a packet of a much better class than that in which we had come from Pittsburg. As this passage does not occupy more than twelve or thirteen hours, we arranged to go ashore that night: not coveting the distinction of sleeping in a state-room, when it was possible to sleep anywhere else (American Notes, p. 165).

There was nothing very interesting in the scenery of this day’s journey, which brought us, at midnight, to Louisville. We slept at the Galt House; a splendid hotel; and were as handsomely lodged as though we had been in Paris, rather than hundreds of miles beyond the Alleghanies. The city presenting no objects of sufficient interest to detain us on our way, we resolved to proceed next day by another steamboat, the Fulton, and to join it, about noon, at a suburb called Portland, where it would be delayed some time in passing through a canal. The interval, after breakfast, we devoted to riding through the town, which is regular and cheerful: the streets being laid out at right angles, and planted with young trees. The buildings are smoky and blackened, from the use of bituminous coal, but an Englishman is well used to that appearance, and indisposed to quarrel with it. There did not appear to be much business stirring; and some unfinished buildings and improvements seemed to intimate that the city had been overbuilt in the ardour of ‘going a-head,’ and was suffering under the re-action consequent upon such feverish forcing of its powers (American Notes, p. 167).

Cairo, Illinois

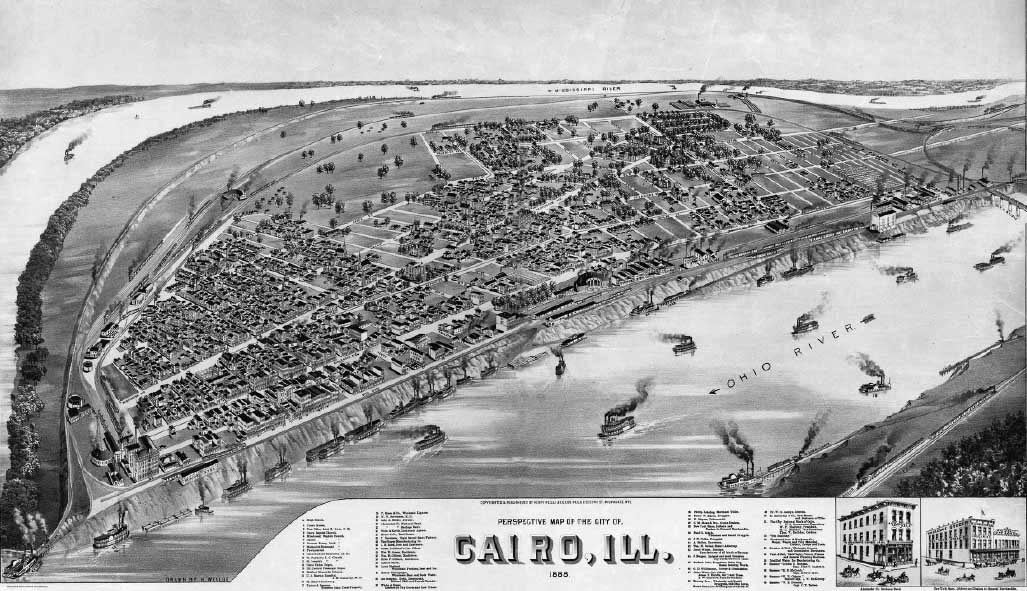

(map I-2) April 9, 15, 1842

Cairo Illinois 1855

American Notes - At length, upon the morning of the third day, we arrived at a spot so much more desolate than any we had yet beheld, that the forlornest places we had passed, were, in comparison with it, full of interest. At the junction of the two rivers, on ground so flat and low and marshy, that at certain seasons of the year it is inundated to the house-tops, lies a breeding-place of fever, ague, and death; vaunted in England as a mine of Golden Hope, and speculated in, on the faith of monstrous representations, to many people’s ruin.10 A dismal swamp, on which the half-built houses rot away: cleared here and there for the space of a few yards; and teeming, then, with rank unwholesome vegetation, in whose baleful shade the wretched wanderers who are tempted hither, droop, and die, and lay their bones; the hateful Mississippi circling and eddying before it, and turning off upon its southern course a slimy monster hideous to behold; a hotbed of disease, an ugly sepulchre, a grave uncheered by any gleam of promise: a place without one single quality, in earth or air or water, to commend it: such is this dismal Cairo (American Notes, p. 171).

Learn more about Charles Dickens in Illinois

Boz in Egypt

At the height of his popularity, English novelist Charles Dickens visited southern Illinois and the American Bottom. It was the ultimate disappointment in a tour that started well in Boston and went downhill from there. "Egypt" or "Little Egypt" is the local nickname for southern Illinois.

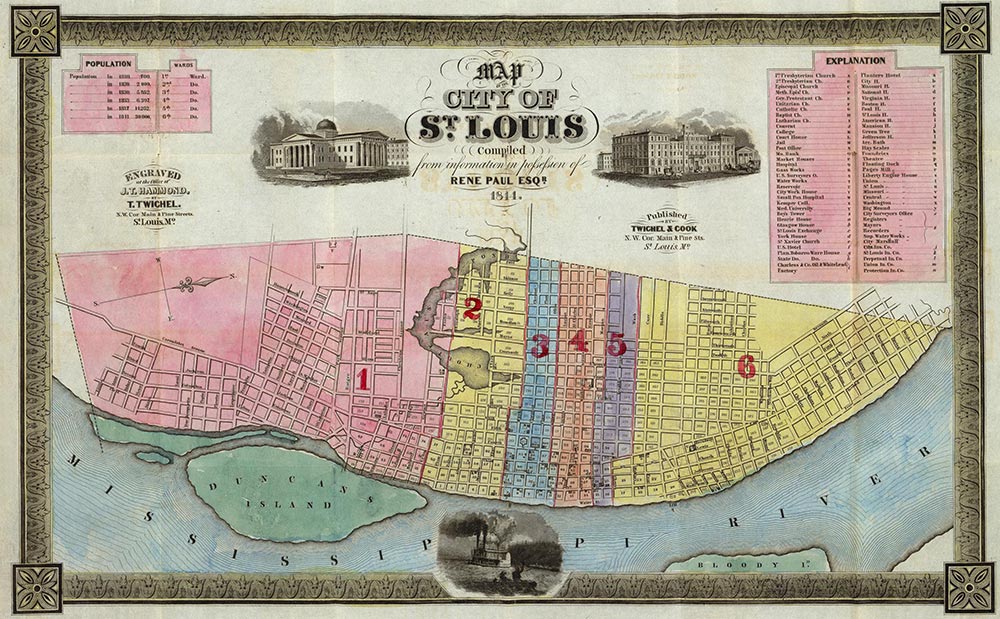

St Louis, Missouri

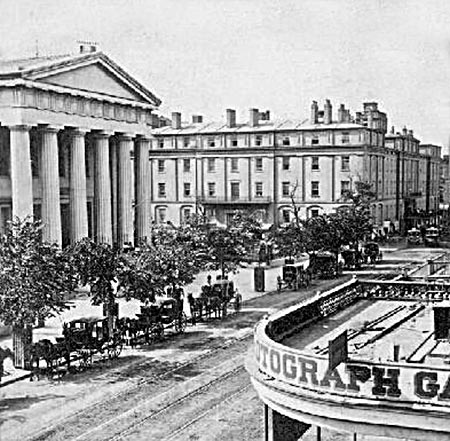

(map H-1) April 10-14, 1842

St Louis Courthouse with Planters' House Hotel beyond

American Notes - We went to a large hotel, called the Planters’ House; built like an English hospital, with long passages and bare walls, and sky-lights above the room-doors for the free circulation of air. There were a great many boarders in it; and as many lights sparkled and glistened from the windows down into the street below, when we drove up, as if it had been illuminated on some occasion of rejoicing. It is an excellent house, and the proprietors have most bountiful notions of providing the creature comforts. Dining alone with my wife in our own room, one day, I counted fourteen dishes on the table at once.

In the old French portion of the town, the thoroughfares are narrow and crooked, and some of the houses are very quaint and picturesque: being built of wood, with tumble-down galleries before the windows, approachable by stairs or rather ladders, from the street. There are queer little barbers’ shops and drinking-houses too, in this quarter; and abundance of crazy old tenements with blinking casements, such as may be seen in Flanders. Some of these ancient habitations, with high garret gable-windows perking into the roofs, have a kind of French shrug about them; and being lop-sided with age, appear to hold their heads askew, besides, as if they were grimacing in astonishment at the American Improvements.

It is hardly necessary to say, that these consist of wharfs and warehouses, and new buildings in all directions; and of a great many vast plans which are still ‘progressing.’ Already, however, some very good houses, broad streets, and marble-fronted shops, have gone so far a-head as to be in a state of completion; and the town bids fair in a few years to improve considerably: though it is not likely ever to vie, in point of elegance or beauty, with Cincinnati.

St Louis riverfront 1840

The Roman Catholic religion, introduced here by the early French settlers, prevails extensively. Among the public institutions are a Jesuit college [St Louis University]; a convent for ‘the Ladies of the Sacred Heart;’ and a large chapel attached to the college, which was in course of erection at the time of my visit, and was intended to be consecrated on the second of December in the present year. The architect of this building, is one of the reverend fathers of the school, and the works proceed under his sole direction. The organ will be sent from Belgium.

In addition to these establishments, there is a Roman Catholic cathedral, dedicated to Saint Francis Xavier; and a hospital, founded by the munificence of a deceased resident, who was a member of that church. It also sends missionaries from hence among the Indian tribes.

The Unitarian church is represented, in this remote place, as in most other parts of America, by a gentleman of great worth and excellence. The poor have good reason to remember and bless it; for it befriends them, and aids the cause of rational education, without any sectarian or selfish views. It is liberal in all its actions; of kind construction; and of wide benevolence.

There are three free-schools already erected, and in full operation, in this city. A fourth is building, and will soon be opened.

No man ever admits the unhealthiness of the place he dwells in (unless he is going away from it), and I shall therefore, I have no doubt, be at issue with the inhabitants of Saint Louis, in questioning the perfect salubrity of its climate, and in hinting that I think it must rather dispose to fever, in the summer and autumnal seasons. Just adding, that it is very hot, lies among great rivers, and has vast tracts of undrained swampy land around it, I leave the reader to form his own opinion (American Notes, p. 174-175).

Looking Glass Prairie-Lebanon, IL

(map H-1) April 12-13, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Mermaid House Hotel in Lebanon, Illinois

While visiting St. Louis, Charles Dickens expressed a desire to see an American prairie before returning east. Finding no shortage of men wishing to accommodate the great author, a group of 13 men set out with Dickens to visit Looking Glass Prairie, a trip of some 30 miles into Illinois. During the trip the entourage stayed at the Mermaid House, an inn in Lebanon, Illinois built by retired sea captain Lyman Adams in 1830. Dickens described the hotel in American Notes: "In point of cleanliness and comfort it would have suffered by no comparison with any village alehouse, of a homely kind, in England."

In American Notes Dickens describes Looking Glass Prairie:

It would be difficult to say why, or how - though it was possibly from having heard and read so much about it - but the effect on me was disappointment. Looking towards the setting sun, there lay, stretched out before my view, a vast expanse of level ground; unbroken, save by one thin line of trees, which scarcely amounted to a scratch upon the great blank; until it met the glowing sky, wherein it seemed to dip: mingling with its rich colours, and mellowing in its distant blue. There it lay, a tranquil sea or lake without water, if such a simile be admissible, with the day going down upon it: a few birds wheeling here and there: and solitude and silence reigning paramount around. But the grass was not yet high; there were bare black patches on the ground; and the few wild flowers that the eye could see, were poor and scanty. Great as the picture was, its very flatness and extent, which left nothing to the imagination, tamed it down and cramped its interest. I felt little of that sense of freedom and exhilaration which a Scottish heath inspires, or even our English downs awaken. It was lonely and wild, but oppressive in its barren monotony. I felt that in traversing the Prairies, I could never abandon myself to the scene, forgetful of all else; as I should do instinctively, were the heather underneath my feet, or an iron-bound coast beyond; but should often glance towards the distant and frequently-receding line of the horizon, and wish it gained and passed. It is not a scene to be forgotten, but it is scarcely one, I think (at all events, as I saw it), to remember with much pleasure, or to covet the looking-on again, in after-life (American Notes, p. 182-183).

St Louis in 1844 showing Bloody Island, which is now part of the Illinois shore

After breakfast, we started to return by a different way from that which we had taken yesterday... The track of to-day had the same features as the track of yesterday...There was the swamp, the bush, and the perpetual chorus of frogs, the rank unseemly growth, the unwholesome steaming earth. Here and there, and frequently too, we encountered a solitary broken-down waggon, full of some new settler's goods. It was a pitiful sight to see one of these vehicles deep in the mire; the axle-tree broken; the wheel lying idly by its side; the man gone miles away, to look for assistance; the woman seated among their wandering household gods with a baby at her breast, a picture of forlorn, dejected patience; the team of oxen crouching down mournfully in the mud, and breathing forth such clouds of vapour from their mouths and nostrils, that all the damp mist and fog around seemed to have come direct from them.

In due time we mustered once again before the merchant tailor's, and having done so, crossed over to the city in the ferry-boat: passing, on the way, a spot called Bloody Island, the duelling-ground of St. Louis, and so designated in honour of the last fatal combat fought there, which was with pistols, breast to breast. Both combatants fell dead upon the ground; and possibly some rational people may think of them, as of the gloomy madmen on the Monks' Mound, that they were no great loss to the community (American Notes, p. 183-184).

Columbus, Ohio

(map G-6) April 21-22, 1842

Neil House, on the right, where Dickens stayed in Columbus

American Notes - Our place of destination in the first instance is Columbus. It is distant about a hundred and twenty miles from Cincinnati, but there is a macadamised [paved] road (rare blessing!) the whole way, and the rate of travelling upon it is six miles an hour [fast for the time].

We start [from Cincinnati] at eight o’clock in the morning, in a great mail-coach, whose huge cheeks are so very ruddy and plethoric, that it appears to be troubled with a tendency of blood to the head. Dropsical it certainly is, for it will hold a dozen passengers inside. But, wonderful to add, it is very clean and bright, being nearly new; and rattles through the streets of Cincinnati gaily (American Notes, p. 188).

We reached Columbus shortly before seven o'clock, and staid there, to refresh, that day and night: having excellent apartments in a very large unfinished hotel called the Neill House, which were richly fitted with the polished wood of the black walnut, and opened on a handsome portico and stone verandah, like rooms in some Italian mansion. The town is clean and pretty, and of course is 'going to be' much larger. It is the seat of the State legislature of Ohio, and lays claim, in consequence, to some consideration and importance (American Notes, p. 192-193).

Upper Sandusky, Ohio

(map F-6) April 22-23, 1842

Overland Inn where Dickens stayed in Upper Sandusky

American Notes - There being no stage-coach next day, upon the road we wished to take, I hired 'an extra,' [private coach] at a reasonable charge to carry us to Tiffin; a small town from whence there is a railroad to Sandusky. This extra was an ordinary four-horse stage-coach, such as I have described, changing horses and drivers, as the stage-coach would, but was exclusively our own for the journey. To ensure our having horses at the proper stations, and being incommoded by no strangers, the proprietors sent an agent on the box, who was to accompany us the whole way through; and thus attended, and bearing with us, besides, a hamper full of savoury cold meats, and fruit, and wine, we started off again in high spirits, at half-past six o'clock next morning, very much delighted to be by ourselves, and disposed to enjoy even the roughest journey.

It was well for us, that we were in this humour, for the road we went over that day [corduroy road], was certainly enough to have shaken tempers that were not resolutely at Set Fair, down to some inches below Stormy. At one time we were all flung together in a heap at the bottom of the coach, and at another we were crushing our heads against the roof. Now, one side was down deep in the mire, and we were holding on to the other. Now, the coach was lying on the tails of the two wheelers; and now it was rearing up in the air, in a frantic state, with all four horses standing on the top of an insurmountable eminence, looking coolly back at it, as though they would say 'Unharness us. It can't be done' (American Notes, p. 193).

Letters - To John Forster 24 Apr 1842 Sandusky, Ohio - The inn at which we halted was a rough log-house. The people were all abed, and we had to knock them up. We had the queerest sleeping-room, with two doors, one opposite the other; both opening directly on the wild black Country, and neither having any lock or bolt. The effect of these opposite doors was, that one was always blowing the other open: an ingenuity in the art of building, which I don't remember to have met with before. You should have seen me, in my shirt, blockading them with portmanteaux, and desperately endeavouring to make the room tidy! But the blockading was really needful, for in my dressing-case I have about £250 in gold; and for the amount of the middle figure in that scarce metal, there are not a few men in the West who would murder their fathers (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 206).

Sandusky, Ohio

(map F-6) April 23-24, 1842

Dickens stayed at the Steamboat Hotel in Sandusky

American Notes - Leaving this town directly after breakfast, we pushed forward again, over a rather worse road than yesterday, if possible, and arrived about noon at Tiffin, where we parted with the extra. At two o'clock we took the railroad; the travelling on which was very slow, its construction being indifferent, and the ground wet and marshy; and arrived at Sandusky in time to dine that evening. We put up at a comfortable little hotel [The Steamboat Hotel] on the brink of Lake Erie, lay there that night, and had no choice but to wait there next day, until a steamboat bound for Buffalo appeared. The town, which was sluggish and uninteresting enough, was something like the back of an English watering-place, out of the season (American Notes, p. 196-197).

We were taking an early dinner at this house, on the day after our arrival, which was Sunday, when a steamboat came in sight, and presently touched at the wharf. As she proved to be on her way to Buffalo, we hurried on board with all speed, and soon left Sandusky far behind us (American Notes, p. 197).

Letters - To John Forster 24 Apr 1842 Sandusky, Ohio - We are in a small house here but a very comfortable one, and the people are exceedingly obliging. Their demeanor in these country parts is invariably morose, sullen, clownish and repulsive. I should think there is not on the face of the earth a people so entirely destitute of humor, vivacity or the capacity of enjoyment. It is most remarkable. Lounging listlessly about bar-rooms, smoking, spitting and lolling on the pavement in rocking chairs outside the shop doors, are the only recreations. Our landlord is from the East. He is a handsome obliging civil fellow. He comes into the room with his hat on, spits in the fire place when he talks, sits down on the sofa with his hat on, pulls out his newspaper and reads, but to all that I am accustomed. He is anxious to please and that's enough (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 207-208).

Cleveland, Ohio

(map F-7) April 24-25, 1842

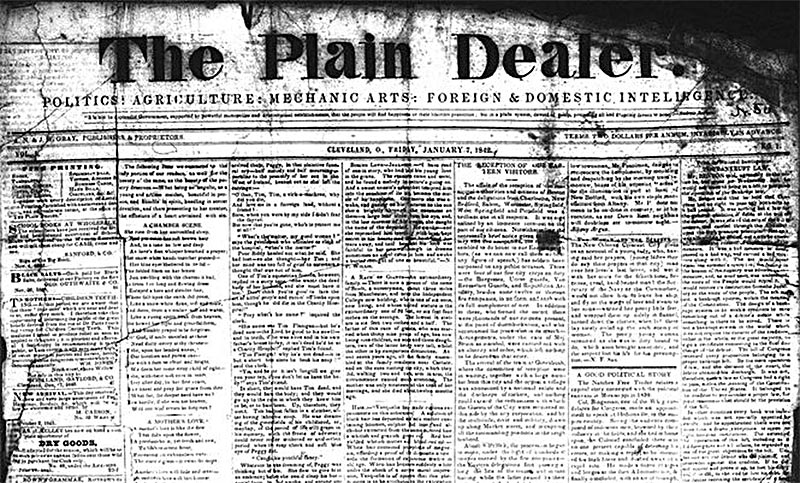

The Plain Dealer, the Cleveland newspaper with which Dickens took exception

American Notes - After calling at one or two flat places, with low dams stretching out into the lake, whereon were stumpy lighthouses, like windmills without sails, the whole looking like a Dutch vignette, we came at midnight to Cleveland, where we lay all night, and until nine o'clock next morning.

I entertained quite a curiosity in reference to this place, from having seen at Sandusky a specimen of its literature in the shape of a newspaper [Plain Dealer], which was very strong indeed upon the subject of Lord Ashburton's recent arrival at Washington, to adjust the points in dispute between the United States Government and Great Britain: informing its readers that as America had 'whipped' England in her infancy, and whipped her again in her youth, so it was clearly necessary that she must whip her once again in her maturity; and pledging its credit to all True Americans, that if Mr. Webster did his duty in the approaching negotiations, and sent the English Lord home again in double quick time, they should, within two years, sing 'Yankee Doodle in Hyde Park, and Hail Columbia in the scarlet courts of Westminster!' I found it a pretty town, and had the satisfaction of beholding the outside of the office of the journal from which I have just quoted. I did not enjoy the delight of seeing the wit who indited the paragraph in question, but I have no doubt he is a prodigious man in his way, and held in high repute by a select circle (American Notes, p. 198).

Letters Vol 3 Pg 209: To John Forster 26 Apr 1842 Sandusky, Ohio - We lay all Sunday night, at a town (and a beautiful town too) called Cleveland; on Lake Erie. The people poured on board, in crowds, by six on Monday morning, to see me; and a party of ‘gentlemen’ actually planted themselves before our little cabin, and stared in at the door and windows while I was washing, and Kate lay in bed. I was so incensed at this...that when the mayor came on board to present himself to me, according to custom, I refused to see him, and bade Mr. Q [Dickens' traveling secretary George Putnam] tell him why and wherefore. His honour took it very coolly, and retired to the top of the wharf, with a big stick and a whittling knife, with which he worked so lustily (staring at the closed door of our cabin all the time) that long before the boat left the big stick was no bigger than a cribbage peg! (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 209)

Niagara Falls, Canada West

(map D-8) April 26 - May 4, 1842

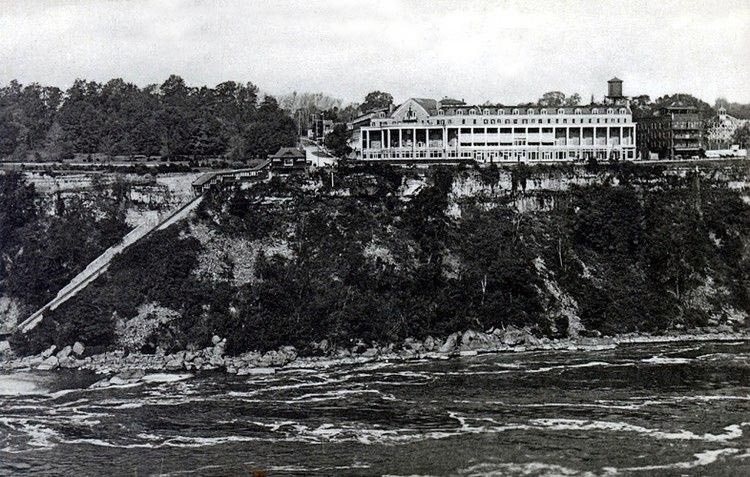

Dickens stayed at the Clifton Hotel in Niagara Falls

American Notes - We called at the town of Erie, at eight o'clock that night, and lay there an hour. Between five and six next morning, we arrived at Buffalo, where we breakfasted; and being too near the Great Falls to wait patiently anywhere else, we set off by the train, the same morning at nine o'clock, to Niagara (American Notes, p. 199).

When we were seated in the little ferry-boat, and were crossing the swollen river immediately before both cataracts, I began to feel what it was: but I was in a manner stunned, and unable to comprehend the vastness of the scene. It was not until I came on Table Rock, and looked - Great Heaven, on what a fall of bright- green water! - that it came upon me in its full might and majesty.

Then, when I felt how near to my Creator I was standing, the first effect, and the enduring one - instant and lasting - of the tremendous spectacle, was Peace. Peace of Mind, tranquillity, calm recollections of the Dead, great thoughts of Eternal Rest and Happiness: nothing of gloom or terror. Niagara was at once stamped upon my heart, an Image of Beauty; to remain there, changeless and indelible, until its pulses cease to beat, for ever (American Notes, p. 199-200).

Dickens' view of the Falls from Clifton Hotel

Letters - To Henry Austin [Dickens' brother-in-law] 1 May 1842 Niagara Falls, Canada - We have had a blessed Interval of quiet in this beautiful place, of which, as you may suppose, we stood greatly in need; not only by reason of our hard travelling for a long time, but on account of the incessant persecution of the people, by land and water; on stage coach, railway car, and steamer; which exceeds anything you can picture to yourself by the utmost stretch of your imagination.

So far, we have had this Hotel [Clifton House] nearly to ourselves. It is a large square house standing on a bold height, with over-hanging eaves like a Swiss Cottage; and a wide, handsome gallery, outside every story. These Colonnades make it look so very light, that it has exactly the appearance of a house built with a pack of cards; and I live in bodily terror, lest any man should venture to step out of a little observatory on the roof, and crush the whole structure with one stamp of his foot.

Our sittingroom (which is large and low, like a Nursery) is on the second floor, and is so close to the Falls that the windows are always wet and dim with Spray (Letters, 1974, v. 3, p. 228-229).

Toronto, Canada West

(map D-8) May 4-6, 1842

Toronto in 1854

American Notes - Our steamboat came up directly this had left the wharf, and soon bore us to the mouth of the Niagara: where the stars and stripes of America flutter on one side, and the Union Jack of England on the other: and so narrow is the space between them that the sentinels in either fort can often hear the watchword of the other country given. Thence we emerged on Lake Ontario, an inland sea; and by half-past six o’clock were at Toronto.

The country round this town being very flat, is bare of scenic interest; but the town itself is full of life and motion, bustle, business, and improvement. The streets are well paved, and lighted with gas; the houses are large and good; the shops excellent. Many of them have a display of goods in their windows, such as may be seen in thriving county towns in England; and there are some which would do no discredit to the metropolis itself. There is a good stone prison here; and there are, besides, a handsome church, a court-house, public offices, many commodious private residences, and a government observatory for noting and recording the magnetic variations. In the College of Upper Canada [Upper Canada College], which is one of the public establishments of the city, a sound education in every department of polite learning can be had, at a very moderate expense: the annual charge for the instruction of each pupil, not exceeding nine pounds sterling [six months wages for a British laborer at the time]. It has pretty good endowments in the way of land, and is a valuable and useful institution (American Notes, p. 205-206).

The time of leaving Toronto for Kingston, is noon. By eight o’clock next morning, the traveller is at the end of his journey, which is performed by steamboat upon Lake Ontario, calling at Port Hope and Coburg, the latter a cheerful thriving little town. Vast quantities of flour form the chief item in the freight of these vessels. We had no fewer than one thousand and eighty barrels on board, between Coburg and Kingston (American Notes, p. 206-207).

Kingston, Canada West

(map C-10) May 7-10, 1842

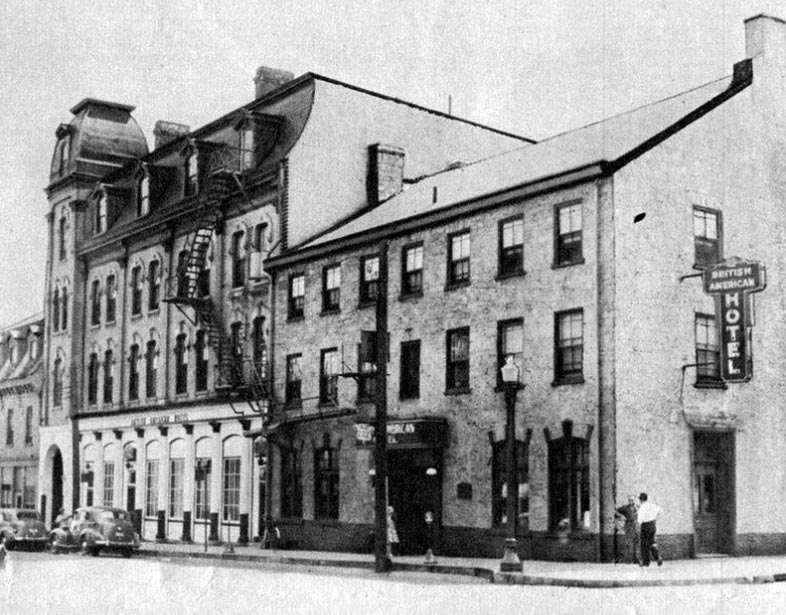

Dickens stayed at Daley's British American Hotel. This view is from 1948, the hotel burned down in 1963

American Notes - [Kingston], which is now the seat of government in Canada, is a very poor town, rendered still poorer in the appearance of its market-place by the ravages of a recent fire. Indeed, it may be said of Kingston, that one half of it appears to be burnt down, and the other half not to be built up. The Government House is neither elegant nor commodious, yet it is almost the only house of any importance in the neighbourhood.

There is an admirable jail here, well and wisely governed, and excellently regulated, in every respect. The men were employed as shoemakers, ropemakers, blacksmiths, tailors, carpenters, and stonecutters; and in building a new prison, which was pretty far advanced towards completion. The female prisoners were occupied in needlework. Among them was a beautiful girl of twenty, who had been there nearly three years. She acted as bearer of secret despatches for the self-styled Patriots on Navy Island, during the Canadian Insurrection [Upper Canada Rebellion]: sometimes dressing as a girl, and carrying them in her stays; sometimes attiring herself as a boy, and secreting them in the lining of her hat. In the latter character she always rode as a boy would, which was nothing to her, for she could govern any horse that any man could ride, and could drive four-in-hand with the best whip in those parts. Setting forth on one of her patriotic missions, she appropriated to herself the first horse she could lay her hands on; and this offence had brought her where I saw her. She had quite a lovely face, though, as the reader may suppose from this sketch of her history, there was a lurking devil in her bright eye, which looked out pretty sharply from between her prison bars.

There is a bomb-proof fort here of great strength [Fort Henry], which occupies a bold position, and is capable, doubtless, of doing good service; though the town is much too close upon the frontier to be long held, I should imagine, for its present purpose in troubled times. There is also a small navy-yard, where a couple of Government steamboats were building, and getting on vigorously (American Notes, p. 207).

Dickinson's Landing, Canada West

(map C-11) May 10, 1842

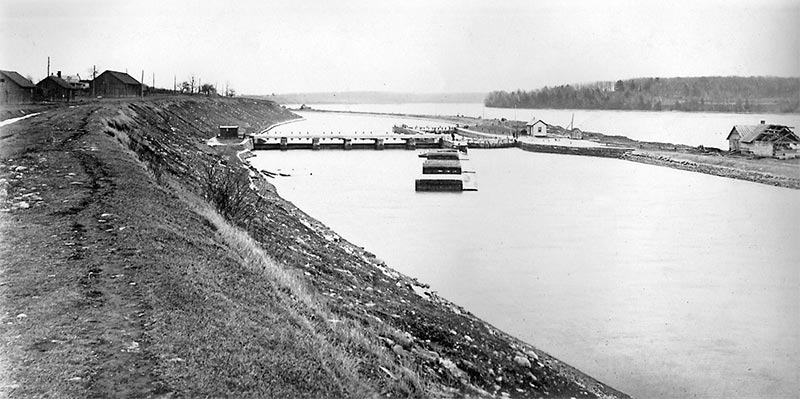

Dickinson's Landing in 1904. The town was flooded in 1958 for the building of the St Lawrence Seaway

American Notes - We left Kingston for Montreal on the tenth of May, at half-past nine in the morning, and proceeded in a steamboat down the St. Lawrence river. The beauty of this noble stream at almost any point, but especially in the commencement of this journey when it winds its way among the thousand Islands, can hardly be imagined. The number and constant successions of these islands, all green and richly wooded; their fluctuating sizes, some so large that for half an hour together one among them will appear as the opposite bank of the river, and some so small that they are mere dimples on its broad bosom; their infinite variety of shapes; and the numberless combinations of beautiful forms which the trees growing on them present: all form a picture fraught with uncommon interest and pleasure.

In the afternoon we shot down some rapids where the river boiled and bubbled strangely, and where the force and headlong violence of the current were tremendous. At seven o'clock we reached Dickenson's Landing, whence travellers proceed for two or three hours by stage-coach: the navigation of the river being rendered so dangerous and difficult in the interval, by rapids, that steamboats do not make the passage. The number and length of those PORTAGES, over which the roads are bad, and the travelling slow, render the way between the towns of Montreal and Kingston, somewhat tedious.

Our course lay over a wide, uninclosed tract of country at a little distance from the river-side, whence the bright warning lights on the dangerous parts of the St. Lawrence shone vividly. The night was dark and raw, and the way dreary enough. It was nearly ten o'clock when we reached the wharf where the next steamboat lay; and went on board, and to bed (American Notes, p. 207-208).

Montreal, Canada East

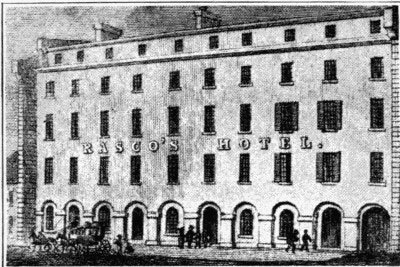

(map B-11) May 11-30, 1842

Dickens stayed at Rasco's Hotel, built in 1836 on St Paul Street Montreal

American Notes - At noon [May 11] we went on board another steamboat, and reached the village of Lachine, nine miles from Montreal, by three o'clock. There, we left the river, and went on by land.

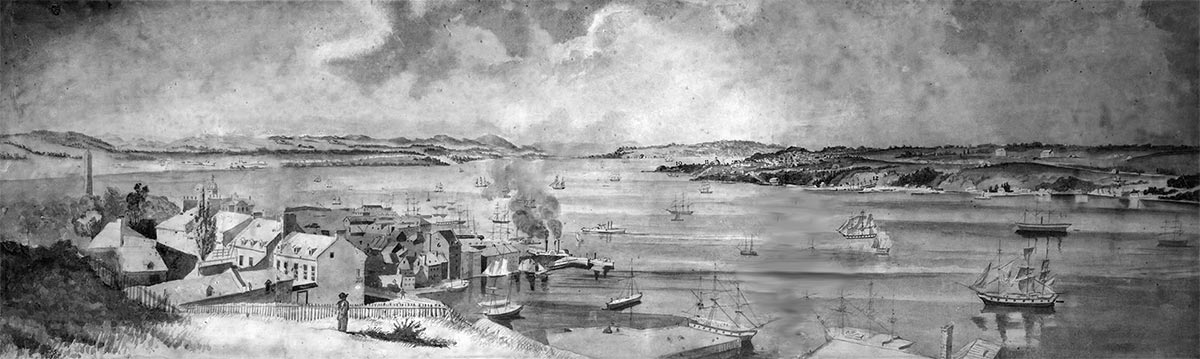

Montreal is pleasantly situated on the margin of the St. Lawrence, and is backed by some bold heights, about which there are charming rides and drives. The streets are generally narrow and irregular, as in most French towns of any age; but in the more modern parts of the city, they are wide and airy. They display a great variety of very good shops; and both in the town and suburbs there are many excellent private dwellings. The granite quays are remarkable for their beauty, solidity, and extent.

There is a very large Catholic cathedral here [Notre Dame Basilica], recently erected with two tall spires, of which one is yet unfinished. In the open space in front of this edifice, stands a solitary, grim-looking, square brick tower, which has a quaint and remarkable appearance, and which the wiseacres of the place have consequently determined to pull down immediately. The Government House is very superior to that at Kingston, and the town is full of life and bustle. In one of the suburbs is a plank road - not footpath - five or six miles long, and a famous road it is too. All the rides in the vicinity were made doubly interesting by the bursting out of spring, which is here so rapid, that it is but a day's leap from barren winter, to the blooming youth of summer (American Notes, p. 209).

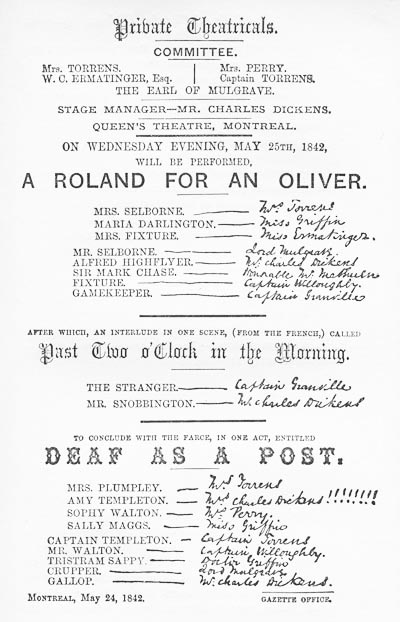

While in Montreal Dickens acted in several private theatricals

Quebec, Canada East

(map A-13) May 27, 1842

Quebec from the Citadel 1852

American Notes - The steamboats to Quebec, perform the journey in the night; that is to say, they leave Montreal at six in the evening, and arrive in Quebec at six next morning. We made this excursion during our stay in Montreal (which exceeded a fortnight), and were charmed by its interest and beauty.

The impression made upon the visitor by this Gibraltar of America: its giddy heights; its citadel suspended, as it were, in the air; its picturesque steep streets and frowning gateways; and the splendid views which burst upon the eye at every turn: is at once unique and lasting (American Notes, p. 209-210).

The city is rich in public institutions and in Catholic churches and charities, but it is mainly in the prospect from the site of the Old Government House, and from the Citadel [La Citadelle de Quebec], that its surpassing beauty lies. The exquisite expanse of country, rich in field and forest, mountain-height and water, which lies stretched out before the view, with miles of Canadian villages, glancing in long white streaks, like veins along the landscape; the motley crowd of gables, roofs, and chimney tops in the old hilly town immediately at hand; the beautiful St Lawrence sparkling and flashing in the sunlight; and the tiny ships below the rock from which you gaze, whose distant rigging looks like spiders’ webs against the light, while casks and barrels on their decks dwindle into toys, and busy mariners become so many puppets: all this, framed by a sunken window in the fortress and looked at from the shadowed room within, forms one of the brightest and the most enchanting pictures that the eye can rest upon (American Notes, p. 210).

Lebanon Springs, New York

(map D-12) Jun 3-4, 1842

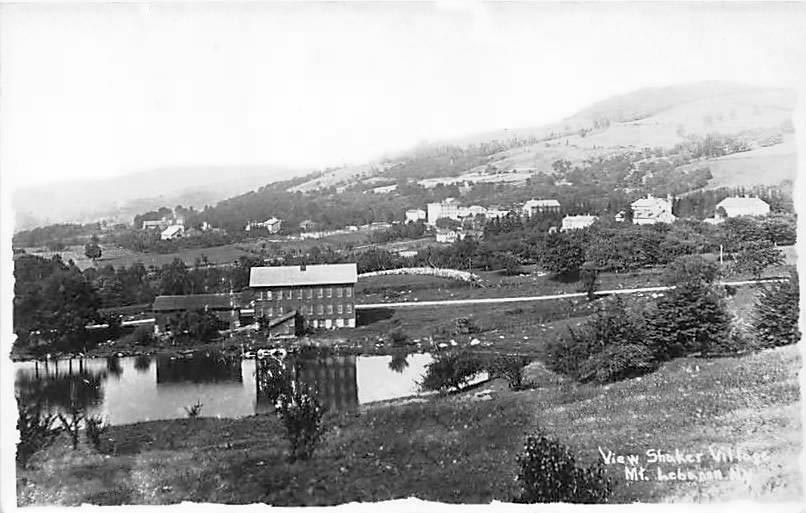

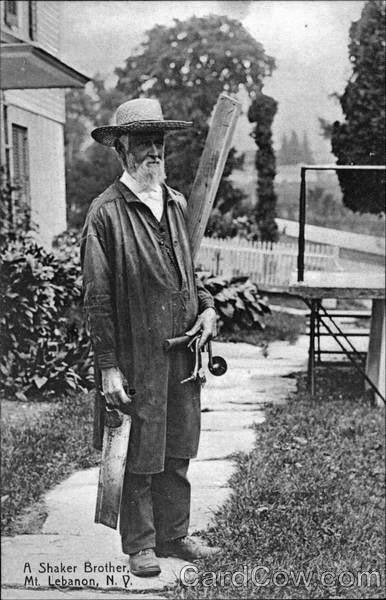

Shaker Village Mount Lebanon, New York

American Notes - We had yet five days to spare before embarking for England, and I had a great desire to see 'the Shaker Village,' which is peopled by a religious sect from whom it takes its name.

To this end, we went up the North River again, as far as the town of Hudson, and there hired an extra [private coach] to carry us to Lebanon, thirty miles distant: and of course another and a different Lebanon from that village where I slept on the night of the Prairie trip (American Notes, p. 214).

Between nine and ten o'clock at night, we arrived at Lebanon which is renowned for its warm baths, and for a great hotel, well adapted, I have no doubt, to the gregarious taste of those seekers after health or pleasure who repair here, but inexpressibly comfortless to me (American Notes, p. 214).

The house is very pleasantly situated, however, and we had a good breakfast. That done, we went to visit our place of destination, which was some two miles off, and the way to which was soon indicated by a finger-post, whereon was painted, 'To the Shaker Village.'

As we rode along, we passed a party of Shakers, who were at work upon the road; who wore the broadest of all broad-brimmed hats; and were in all visible respects such very wooden men, that I felt about as much sympathy for them, and as much interest in them, as if they had been so many figure-heads of ships. Presently we came to the beginning of the village, and alighting at the door of a house where the Shaker manufactures are sold, and which is the headquarters of the elders, requested permission to see the Shaker worship.

Pending the conveyance of this request to some person in authority, we walked into a grim room, where several grim hats were hanging on grim pegs, and the time was grimly told by a grim clock which uttered every tick with a kind of struggle, as if it broke the grim silence reluctantly, and under protest. Ranged against the wall were six or eight stiff, high-backed chairs, and they partook so strongly of the general grimness that one would much rather have sat on the floor than incurred the smallest obligation to any of them.

Shaker Brother

Presently, there stalked into this apartment, a grim old Shaker, with eyes as hard, and dull, and cold, as the great round metal buttons on his coat and waistcoat; a sort of calm goblin. Being informed of our desire, he produced a newspaper wherein the body of elders, whereof he was a member, had advertised but a few days before, that in consequence of certain unseemly interruptions which their worship had received from strangers, their chapel was closed to the public for the space of one year.

As nothing was to be urged in opposition to this reasonable arrangement, we requested leave to make some trifling purchases of Shaker goods; which was grimly conceded. We accordingly repaired to a store in the same house and on the opposite side of the passage, where the stock was presided over by something alive in a russet case, which the elder said was a woman; and which I suppose WAS a woman, though I should not have suspected it (American Notes, p. 215-216).

Leaving the Shaker village with a hearty dislike of the old Shakers, and a hearty pity for the young ones: tempered by the strong probability of their running away as they grow older and wiser, which they not uncommonly do: we returned to Lebanon, and so to Hudson, by the way we had come upon the previous day. There, we took the steamboat down the North River towards New York... (American Notes, p. 207)218

West Point, New York

(map E-12) Jun 4-6, 1842

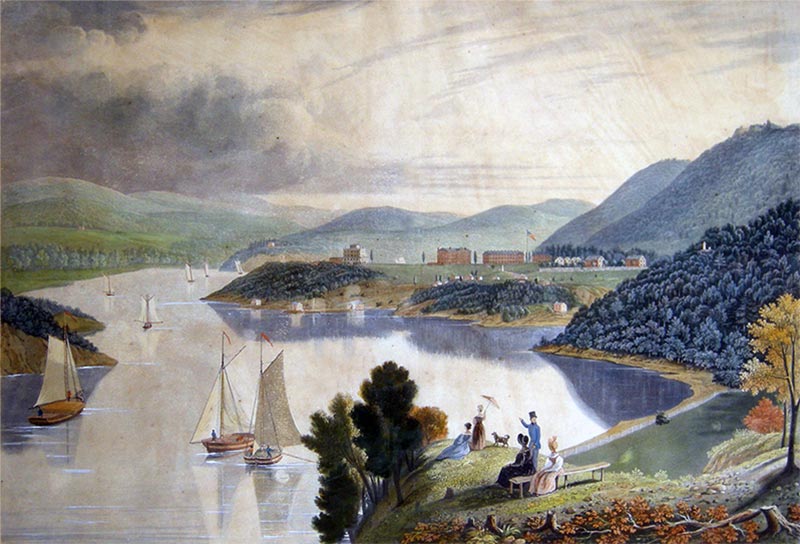

West Point 1841

American Notes - We took the steamboat down the North River towards New York, but stopped, some four hours’ journey short of it, at West Point, where we remained that night, and all next day, and next night too.

In this beautiful place: the fairest among the fair and lovely Highlands of the North River: shut in by deep green heights and ruined forts, and looking down upon the distant town of Newburgh, along a glittering path of sunlit water, with here and there a skiff, whose white sail often bends on some new tack as sudden flaws of wind come down upon her from the gullies in the hills: hemmed in, besides, all round with memories of Washington, and events of the revolutionary war: is the Military School of America.

It could not stand on more appropriate ground, and any ground more beautiful can hardly be. The course of education is severe, but well devised, and manly. Through June, July, and August, the young men encamp upon the spacious plain whereon the college stands; and all the year their military exercises are performed there, daily. The term of study at this institution, which the State requires from all cadets, is four years; but, whether it be from the rigid nature of the discipline, or the national impatience of restraint, or both causes combined, not more than half the number who begin their studies here, ever remain to finish them.

The number of cadets being about equal to that of the members of Congress, one is sent here from every Congressional district: its member influencing the selection. Commissions in the service are distributed on the same principle. The dwellings of the various Professors are beautifully situated; and there is a most excellent hotel for strangers, though it has the two drawbacks of being a total abstinence house (wines and spirits being forbidden to the students), and of serving the public meals at rather uncomfortable hours: to wit, breakfast at seven, dinner at one, and supper at sunset (American Notes, p. 218-219).