The Charles Dickens Page

Charles Dickens'

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities - A Story of the French Revolution

A Tale of Two Cities - Published in weekly parts Apr 1859 - Nov 1859

Charles Dickens' twelfth novel was published in his new weekly journal, All the Year Round, without illustrations. Simultaneously with the weekly parts, the novel was also published in monthly parts with illustrations by Hablot Browne. An American edition was also published, in slightly later weekly parts (May to December 1859), in Harper's Weekly (Patten, 1978, p. 276).

The novel, which begins It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, is set against the backdrop of the French Revolution and Dickens researched the historical background meticulously, using his friend Thomas Carlyle's History of the French Revolution as a reference (Goldberg, 1972, p. 101). This historical accuracy, with less reliance on character development and humor, led to the rather un-Dickensian feel of the book (Watts, 1991, p. 115).

Plot

(contains spoilers)

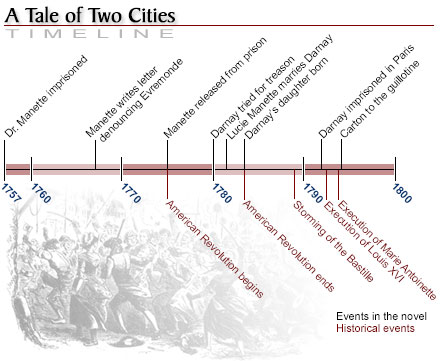

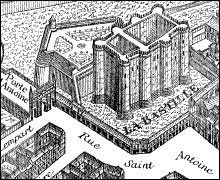

The year is 1775 and Dr Alexandre Manette, imprisoned unjustly 18 years ago, has been released from the Bastille prison in Paris. His daughter, Lucie, who had thought he was dead, and Jarvis Lorry, an agent for Tellson's Bank, which has offices in London and Paris, bring him to England.

Skip ahead 5 years to 1780. Frenchman Charles Darnay is on trial for treason, accused of passing English secrets to the French and Americans during the American Revolution. He is represented by Stryver and is acquitted when eyewitnesses prove unreliable partly because of Darnay's resemblance to barrister Sydney Carton.

In the years leading up to the fall of the Bastille in 1789 Darnay, Carton, and Stryver all fall in love with Lucie Manette. Carton, an irresponsible and unambitious character who drinks too much, tells Lucie that she has inspired him to think how his life could have been better and that he would make any sacrifice for her. Stryver, Carton's barrister friend, is persuaded against asking for Lucie's hand by Mr Lorry, now a close friend to the Manettes. Lucie marries Darnay and they have a daughter.

Meanwhile, in France, Darnay's uncle the Marquis St. Evremonde is murdered in his bed for crimes committed against the people. Charles has told Dr. Manette of his relationship to the French aristocracy, but no one else.

By 1792 the revolution has escalated in France. Mr Lorry receives a letter at Tellson's Bank addressed to the Marquis St. Evremonde whom no one seems to know. Darnay sees the letter and tells Lorry that he knows the Marquis and will deliver it. The letter is from a friend, Gabelle, wrongfully imprisoned in Paris and asked the Marquis (Darnay) for help. Knowing that the trip will be dangerous, Charles feels compelled to go and help his friend. He leaves for France without telling anyone the real reason.

On the road to Paris, Darnay (St Evremonde) is recognized by the mob and taken to prison in Paris. Mr Lorry, in Paris on business, is joined by Dr. Manette, Lucie, Miss Pross, and later, Sydney Carton.

Dr. Manette has influence over the citizens due to his imprisonment in the Bastille and is able to have Darnay released but he is retaken the next day on a charge by the Defarges and is sentenced to death within 24 hours.

Sydney Carton has influence on one of the jailers and is able to enter the cell, drug Darnay, exchange clothes, and have the jailer remove Darnay, leaving Carton to die in his stead.

On the guillotine Carton peacefully declares "It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known" (A Tale of Two Cities, 1859, p. 358).

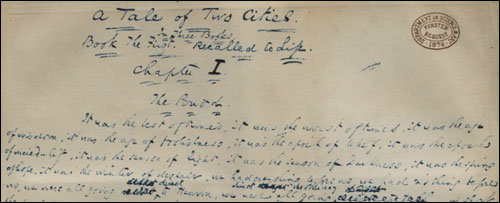

The original manuscript of A Tale of Two Cities at the Victoria and Albert Museum

Complete List of Characters

Character descriptions contain spoilers

A Tale of Two Cities Links:

The Victorian Web

Teaching A Tale of Two Cities

Bartleby.com

SparkNotes - Excellent!

Wikipedia - A Tale of Two Cities

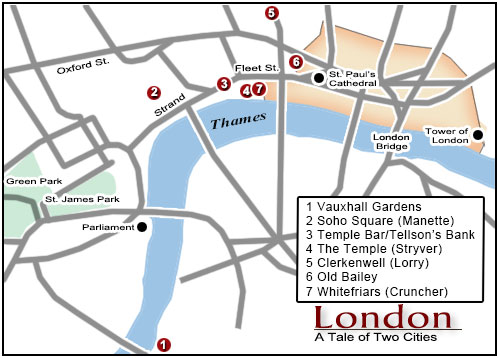

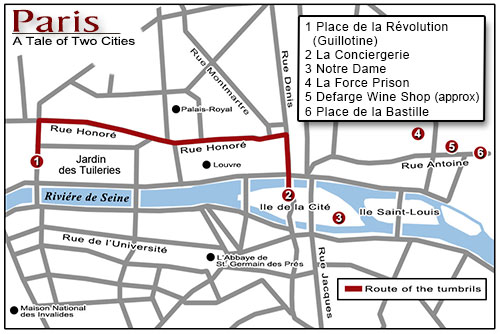

Locations in A Tale of Two Cities

Further Information

The Two Cities

Places in the novel

Resurrection Men

Dickens has Jerry Cruncher, "an honest tradesman" by day, spend his evenings as a resurrection man, or body-snatcher.

Dickens has Jerry Cruncher, "an honest tradesman" by day, spend his evenings as a resurrection man, or body-snatcher.

By the eighteenth century the demand for fresh corpses for use in medical training had outstripped the supply, which could only legally be obtained from executed murderers. The dread of dissection after execution being considered an additional deterrent for would-be murderers.

To supply this demand for fresh corpses surgeons and anatomists turned to resurrection men or body snatchers. Strange bedfellows indeed!

Ruth Richardson, in her book Death, Dissection, and the Destitute described a common method these men used to obtain fresh corpses:

"Bodysnatchers invariably worked in small gangs, to allow at least one person to be on the look-out for potential danger. Freshly-filled graves meant that in general the digging was easy, as the earth was still loose, and not yet compacted by settling. Canvas would sometimes be laid by the grave to receive the displaced earth, so as to leave none on surrounding turf. A hole would be dug at the head of the grave, down to the coffin, and hooks or a crow-bar inserted under the lid. The weight of earth on the rest of the lid acted as a counter-weight, so that when pressure was exerted the lid invariably snapped across and the body could be hoisted out of the grave with ropes. Sacking would be heaped over the lid beforehand to deaden the sound of cracking wood. At this stage in the proceedings, the corpse should in principle have been stripped and the grave-clothes thrown back, before the earth was shoved back into place, and the body trussed up neck and heels in a sack" (Richardson, 1987, p. 59).

It is interesting to note that a corpse was not considered to be property thus the stealing of a corpse was only a misdemeanor. That was the reason that the grave-clothes, and any other articles about the corpse were thrown back in the grave, the taking of which would be considered a felony.

Cases arose in the early nineteenth century of surgeons buying fresh corpses whom they doubtless knew had been murdered for the purpose.

Parliament, seeking an end to this heinous practice, passed the Anatomy Act of 1832. Under this law the bodies of unclaimed dead from workhouses could be used for dissection. The reaction to this practice was widespread uprising in the workhouses as what was viewed as a punishment to murder was now considered a judgement on the poor (Richardson, 1987).

La Guillotine

Although a mechanical device used for beheadings had been in use for centuries, the guillotine is best known for its use during the Reign of Terror in France during the French Revolution where the device, which takes its name from Dr. Guillotin, was used for thousands of "humane" beheadings. The guillotine was still in use well into the 20th century (Wikipedia).

Although a mechanical device used for beheadings had been in use for centuries, the guillotine is best known for its use during the Reign of Terror in France during the French Revolution where the device, which takes its name from Dr. Guillotin, was used for thousands of "humane" beheadings. The guillotine was still in use well into the 20th century (Wikipedia).

Dickens witnessed a beheading by guillotine in Rome in 1845 which he described in Pictures from Italy:

"[The prisoner] immediately kneeled down, below the knife. His neck fitting into a hole, made for the purpose, in a cross plank, was shut down, by another plank above; exactly like the pillory. Immediately below him was a leathern bag. And into it his head rolled instantly.

...The eyes were turned upward, as if he had avoided the sight of the leathern bag, and looked to the crucifix. Every tinge and hue of life had left it in that instant. It was dull, cold, livid, wax. The body also.

There was a great deal of blood... A strange appearance was the apparent annihilation of the neck. The head was taken off so close, that it seemed as if the knife had narrowly escaped crushing the jaw, or shaving off the ear; and the body looked as if there were nothing left above the shoulder" (American Notes-Pictures from Italy, p. 391).

Thomas Carlyle

The French Revolution

Dickens met Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle in 1840 and the two became fast friends. An essayist, satirist, and historian, Carlyle was a tremendous influence on the younger Dickens. Dickens actively sought Carlyle's approval and the influence of Carlyle on Dickens' later work is unmistakable. Although the crusty Carlyle at times dismissed Dickens as merely an entertainer, he truly loved the exuberant, full-of-life writer (Johnson, 1952, p. 316).

Dickens met Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle in 1840 and the two became fast friends. An essayist, satirist, and historian, Carlyle was a tremendous influence on the younger Dickens. Dickens actively sought Carlyle's approval and the influence of Carlyle on Dickens' later work is unmistakable. Although the crusty Carlyle at times dismissed Dickens as merely an entertainer, he truly loved the exuberant, full-of-life writer (Johnson, 1952, p. 316).

Dickens jokingly claimed to have read Carlyle's The French Revolution (1837) 500 times. He used it as his main historical reference in writing A Tale of Two Cities, a book which Carlyle called "wonderful" athough complaining that he had to read it by "teaspoonfuls" (Johnson, 1952, p. 955).

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas CarlyleThe French Revolution

Tellson's Bank at Temple Bar

Tellson's Bank, in A Tale of Two Cities, is situated at Temple Bar where the City of London meets the City of Westminster and Fleet Street becomes the Strand. Child & Co bank has operated from this site since the 1660s and Dickens used the bank as a model for Tellson's.

Temple Bar, an archway designed by Christopher Wren, was erected on the spot in 1672, replacing a wooden archway damaged in the great fire of 1666. By 1878 Temple Bar had become a impediment to the increasing traffic in the area and was removed to a private residence. It was brought back to the City of London in 2003 and installed in St. Pauls Churchyard. A monument with a dragon atop marks the spot where Temple Bar stood in Dickens' time.

The Old Men of Tellson's

"Cramped in all kinds of dun cupboards and hutches at Tellson's, the oldest of men carried on the business gravely. When they took a young man into Tellson's London house, they hid him somewhere till he was old. They kept him in a dark place, like a cheese, until he had the full Tellson flavour and blue-mould upon him. Then only was he permitted to be seen, spectacularly poring over large books, and casting his breeches and gaiters into the general weight of the establishment" (A Tale of Two Cities, p. 50-51).

Child and Co Bank

Site of Tellson's Bank

A Date with Dickens

A Date with Dickens

Oprah chooses Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations Dec 2010

Recalled to Life

Dr Manette in the Bastille - by Phiz

Being "recalled to life" is a major theme throughout A Tale of Two Cities. In fact, Dickens toyed with the idea of titling the book Recalled to Life.

Dr. Manette's release from the Bastille, Charles Darnay's release after the trial for treason, and his later escape from the French prison, are examples of this theme. Also, Roger Cly's fake burial and Jerry Cruncher's nocturnal occupation as a 'resurrection man' follow this theme.

Sydney Carton, on his way to the guillotine, envisions himself 'recalled to life' in the person of the Darnay's future son.

As Carton is contemplating his eminent sacrifice he finds peace in the passage from John 11:25-26:

"I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live. And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die" (KJV, John 11: 25-26).

Charles Dickens' life during the serialization of A Tale of Two Cities

Apr 1859 - Nov 1859Dickens' age: 47

April 1859

Dickens published A Tale of Two Cities in his new weekly journal All the Year Round hoping to retain readers of his previous weekly, Household Words. By its fifth issue sales of All the Year Round were triple that of Household Words (Johnson, 1952, p. 946).

November 1859

Dickens attempted to persuade George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) to contribute a story for All the Year Round. After some negotiation Eliot declined (Kaplan, 1988, p. 430-431).

Quote:

"A wonderful fact to reflect upon, that every human creature is constituted to be that profound secret and mystery to every other. A solemn consideration, when I enter a great city by night, that every one of those darkly clustered houses encloses its own secret; that every room in every one of them encloses its own secret; that every beating heart in the hundreds of thousands of breasts there, is, in some of its imaginings, a secret to the heart nearest it!" (A Tale of Two Cities, 1859, p. 10)

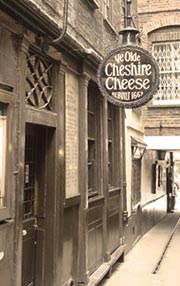

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese

After Darnay is acquitted of treason he accompanies Sydney Carton "down Ludgate hill to Fleet Street, and so, up a covered way, into a tavern. Here, they were shown into a little room, where Charles Darnay was soon recruiting his strength with a good plain dinner and good wine" (A Tale of Two Cities, p. 77).

After Darnay is acquitted of treason he accompanies Sydney Carton "down Ludgate hill to Fleet Street, and so, up a covered way, into a tavern. Here, they were shown into a little room, where Charles Darnay was soon recruiting his strength with a good plain dinner and good wine" (A Tale of Two Cities, p. 77).

This was almost certainly Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, rebuilt after the great fire of 1666 and a favorite of Dickens.

Read about a visit Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese by Joseph Pennell for Harper's Weekly in November 1887.

Charles-Henri Sanson

"Sixty-three to-day. We shall mount to a hundred soon. Samson and his men complain sometimes, of being exhausted. Ha, ha, ha! He is so droll, that Samson. Such a Barber!" (A Tale of Two Cities, p. 296)

Charles-Henri Sanson, (15 February 1739 – 4 July 1806) referred to as Samson in the book, was the Royal Executioner of France during the reign of King Louis XVI, and High Executioner of the First French Republic. He administered capital punishment in the city of Paris for over forty years, and by his own hand executed nearly 3,000 people, including the King himself.

Izaak Walton

Jerry Cruncher, in his nighttime ruse of "going fishing", is described by Dickens as a deciple of Izaak Walton. Walton's fishing bible, The Compleat Angler, was first published in 1653.

Saint Antoine

Saint Antoine, where the Defarge's wine shop is located, became part of Paris in 1702. The Bastille prison stood at its western edge.

Evrèmonde

Evrèmondeby Diana Mayer

Sequel to A Tale of Two Cities

Press Release (34k pdf)